Florentine Fare: the history behind this Italian cuisine

Polpette di Trippa, tripe meatballs; a Florentine favourite.

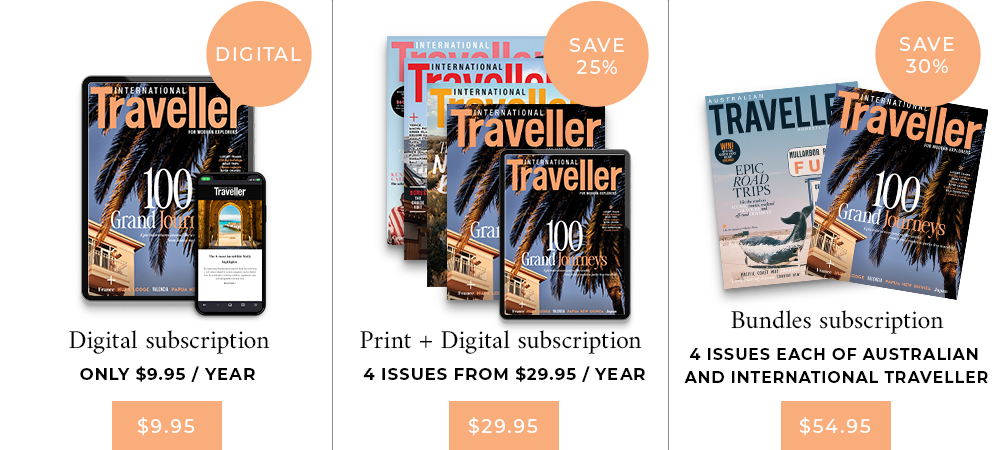

Italian food has conquered the world, but the earthy, sometimes austere cuisine of Florence remains largely undiscovered.

Tuscan transplant Emiko Davies set about changing all that with her tome Florentine: The True Cuisine of Florence.

The Florentines, like most Italians, have a very important relationship with their food.

There are rules about what can be eaten when, with what accompaniments and in what particular order.

Seasons and traditions play an important role in the kitchen and you can easily tell the time of year by simply looking at a Florentine menu, bakery window or market stall.

Florence’s side streets are a rabbit warren of restaurants and cafes.

Florentine cuisine is earthy and rustic, at times even austere. Not extravagant, but reliable and modest. Sincere and straightforward. Although simple, it is prepared with pride and care, and makes particularly good use of bread and olive oil, two of the cuisine’s staple ingredients.

With a nod to medieval origins, many dishes reflect the ethos of not letting anything go to waste. The Florentines are masters of thrift, using up what others would normally throw out. They make the most of stale bread, chicken livers, lampredotto (abomasum tripe) and even roosters’ combs – although this once popular Renaissance dish, known as cibreo, is almost extinct today.

All of these ingredients are carefully prepared in characteristically simple ways, unique to Florence, in dishes such as ribollita, crostini di fegatini and lampredotto panini.

Not only are these ingredients a model of economy in the kitchen, but they are also exalted, with these well-known dishes being elevated to hero status in the city.

Florentine food journalist Leonardo Romanelli points out that the only weakness in the local cuisine is dessert.

Missing a sweet tooth, many of Florence’s traditional sweets are either bread-based, such as the autumnal schiacciata all’uva (grape focaccia), pandiramerino (raisin and rosemary buns) and schiacciata alla fiorentina (a yeasted cake dusted with powdered sugar); or they are deep-fried and are strictly a winter Carnival treat, such as cenci and frittelle (rice fritters).

Traditional Florentine cuisine is as old as the city’s Renaissance architecture.

Zuccotto is the closest thing to a proper dessert, resembling a bright pink version of the dome of Florence’s Duomo, with Alchermes-dipped sponge encasing a rich ricotta and chocolate filling. And then there are cantuccini (almond biscotti), the preferred way to end a meal at a Florentine table with a glass of sweet vin santo for dipping and inspiring conversation.

The Renaissance was a period of enormous change, not only in the world of art and architecture, but also in gastronomy.

The same sensibility that was being used in art was influencing dishes in Florentine kitchens, and the subsequent banquets in noble palazzi.

During this time, cooking techniques improved and became more sophisticated, while aesthetics and presentation of food became more important than ever.

Apparently Michelangelo would request seasonal pecorino cheese (known as marzolino cheese) be sent to him from Florence when he was working in Rome.

The discovery of the New World in 1492 also brought a plethora of new and exotic ingredients to experiment with in the kitchen.

These ingredients gave rise to more refined and elegant food.

At the 1469 wedding of Lorenzo the Magnificent (1449–1492) – Florence’s beloved ruler and benefactor to artists such as Michelangelo and Botticelli – there was a deliberately modest public feast, where 400 of the town’s citizens were invited to share in the event.

Three years earlier, for the marriage of Lorenzo’s sister, Nannina, into Florence’s powerful Rucellai family, celebrations were more extravagant, yet still refined.

Fifty cooks fed over 500 people over three days. Boiled tongue and biancomangiare were served at the first course: a delicate dish and enormously popular in the Renaissance, biancomangiare was made with finely pounded, poached chicken breast cooked with almond milk, white bread and sugar until creamy, then garnished with rosewater or spices.

It had a beautifully creamy texture and a delicate but perfectly balanced flavour, and was made using techniques that ensured that it remained perfectly white in colour.

It is a wonderful example of how the culinary arts went through a Renaissance as much as the rest of the arts, taking a giant leap from the rough gruels of the Middle Ages.

This course was followed by roast meats garnished with rosewater, then cold meats and jellied fish, and then a second roast. The food, as characterised by this period and by its leaders, was splendid but not at all over the top.

[Florence’s] unique and unpretentious cuisine remains little known in the gastronomic world – under the shadow of the Tuscan region as a whole, perhaps.

But in the same way that history weaves its way into anything you explore in depth in Florence, so is the cuisine formed by its fantastic history.

This is an edited extract from Florentine: The True Cuisine of Florence by Emiko Davies, Hardie Grant Books, $49.95.

Florence’s best restaurants

Recommended by the exquisite Palazzo Vecchietti Hotel.

- Parione

Traditional dishes just a few steps from the Ponte Vecchio; parione.net - Buca Mario

Established in 1886 and still run by the Pasquetti family, who serve up the ‘show stopper’ thick-cut Florentine steak; bucamario.com - Buca Lapi

The menu here boasts ribollita and tripe, and wild boar with polenta; bucalapi.com - Trattoria 13 Gobbi

House specialties here include rigatonis served in ceramic tureen and beef cut for two served on the stump; casatrattoria.com - Cammillo Trattoria

Order from the daily menu for the best seasonal dishes; Borgo San Jacopo Vecchio, 57R

LEAVE YOUR COMMENT