White Nights in sleepless St Petersburg

The Winter Palace: 1786 doors, 1945 windows, 1500 rooms and 117 staircases.

Sleep is totally optional, if impossible, during St Petersburg’s White Nights. Laura Parker reveals the never-ending possibilities of Russia’s greatest city in summer.

It’s early evening in St. Petersburg. I’m in Moscow Square, in the city’s south, watching 200 Russian youths splash around in an industrial-sized fountain with supersoakers, buckets and Tupperware containers.

In the middle of the square, an imposing statue of Lenin stands guard. It’s uncertain whether he would have approved of the anarchic scenes.

The water skirmish is tempting, to escape the mugginess of the afternoon. A spectating parent tells me public water fights are common in St. Petersburg during the White Nights, or Belye Nochi, from early June to mid-July.

It’s a way for the teenagers to pass the time when the sun sets well after 2am. And how do adults pass the endless hours of light? “Vodka,” he says, laughing.

St. Petersburg is relatively young for a European city. Founded by Tsar Peter the Great in 1703, it served as the country’s capital from 1732 to 1918.

It is Russia’s second largest city after Moscow and the country’s cultural epicentre, home to more than 500 museums, theatres, concert halls, galleries and architectural complexes. Tchaikovsky, Prokofiev, Stravinsky, Dostoyevsky, Nabokov, Nikolai Gogol, Marc Chagall, Peter Carl Faberge and Rudolf Nureyev all lived and worked here.

The city’s historical centre is dominated by the green and white Winter Palace, the official residence of the Russian monarchy until 1917 (it’s now The Hermitage – a museum of art and culture).

The building itself is a striking mix of Baroque ostentatiousness and neoclassical purity, testament to Peter the Great’s efforts to modernise Russia in the 18th century. The Savior of the Spilled Blood, the candy-coloured onion dome church depicted on all the postcards, sits in the middle of it all, a formidable example of medieval Russian architecture in a predominantly neoclassical city.

Built to commemorate the assassination of Tsar Alexander II, the church’s walls are covered in 7000 square metres of mosaic depicting Biblical scenes.

Nearby, row upon row of brightly coloured façades line the streets. Italian architect Carlo Rossi was responsible for many of these, including one of the oldest buildings in the city, the Grand Hotel Europe.

The hotel, part of Orient-Express, is a destination itself: it’s where Tchaikovsky spent his honeymoon, where Bernard Shaw dined with Maxim Gorky, and where the Romanov descendants stay when they’re in town. (They have their own suite.)

Even the dullest of establishments are housed in opulence: I once walked into a building convinced it was a point of interest – its façade certainly suggested so – only to discover it was a manufacturer of rubber products.

Ever changing, ever busy city

I sit down at a café near the church and watch people go past on their way to work. The waitress tells me the city is changing. “More people visit now,” she says. “People like our city.”

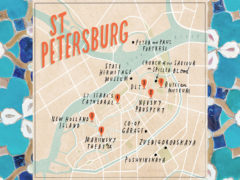

The growing traveller interest is seen most clearly around Nevsky Prospekt, the city’s main shopping strip. Locals mingle with tourists, street vendors peddle merchandise – unsurprisingly, Babushka dolls are the souvenir du jour – and tour guides from the local canal cruise companies wave brochures and discounts at whoever will listen.

I wander in and out of fashion boutiques, overpriced souvenir stores and English language bookstores.

On weekends, during the white nights, several blocks of Nevsky Prospekt are closed to traffic making way for food vendors and street performers who sing and dance to traditional Russian songs, while rollerskaters leap over those brave enough to lie on the ground for them. (Rollerskating is still big in Russia.)

One of Nevsky’s newest bars, Biblioteka is a three-level affair – a burger joint on the bottom, a sit-down restaurant on the middle floor and a candlelit library-themed bar with plush lounges on the top level.

By 1:30am, the place is full of Russian hipsters swigging lager from tall glasses. I start chatting to a couple of students – young people in St. Petersburg are friendly; the older locals seem to display all the gruffness of a bad ’80s ‘commie’ movie.

In a quieter corner of the city I find the Conservatory, a sturdy neoclassical building with a pale blue façade erected on the site of the old Bolshoi Theatre.

The door is open and there’s no one around, so I peek inside. It’s empty; there’s a grand, carpeted staircase leading to a second landing where chandeliers hang from a frescoed ceiling.

A poster reveals Swan Lake is playing tomorrow night. This particular production is part of the White Nights Festival, a month-long program of ballet, concerts and opera performances. It’s just one of more than 100 cultural festivals the city hosts every year.

Outside, it’s almost 9pm and the sun is still out. On my way through the Palace Square I stumble upon a simple open-air production of Faust. With the Winter Palace as a backdrop, it’s magnificent.

Up close with Da Vinci

The next morning, The Hermitage is ridiculously crowded – I stand in line for five minutes to get a closer look at a Da Vinci. But the real gems of the collection are found away from crowds and queues, including an entire room dedicated to drinking games from the 11th century.

Outside the city, Peterhof, Peter the Great’s palace, is a grand estate where the manicured gardens, fountains, grand walkways and arches are the highlight.

The tsar’s daughter Elizabeth also used the palace to store her excessive fetish for fashion: she reportedly owned 15,000 dresses, changed outfits four times a day, and never wore the same dress twice.

Today’s fashion in Russia suggests Elizabeth did not pass on her sartorial extravagance: at the ballet that night, I see only a few people not wearing denim.

The ballet itself is excellent, but the real action happens in the orchestra pit: a percussion apprentice, triangle in hand, makes his move too soon while following a Tchaikovsky score and chastises himself as he pulls away from the microphone.

On the way home I realise I have yet to experience what guidebooks list as an unmissable event in St. Petersburg. There are over a thousand bridges in this city, connecting the various districts to one another.

Another brainchild of Peter the Great, who envisioned people moving around by boat in the summer, and on sledges in winter. During summer, at around 2am each morning, 13 of the main bridges in the city are raised to allow cruise ships to pass through, and are not lowered again until sunrise.

I head to Trinity Bridge, an art nouveau structure connecting central St. Petersburg to the Petrograd. I take up a position on the embankment, and watch as the crowds slowly gather.

The sense of ritual renders it beautiful: the lights on the bridge turning on one-by-one, people waving goodbye as they go their separate ways, pedestrians and cars hurrying to make it across in time.

The bridge opening ritual signals the end of a very long day. At 3am, when it’s finally truly dark, St Petersburg takes a short rest. In three hours, another day will begin.

The details

How to get there: Qantas, Emirates and Singapore Airlines all fly daily from Australia to St. Petersburg via Dubai, Paris or London. Expect to pay around $2800 in high season (summer) and around $1800 in low season (winter).

When to go: Since winter temperatures can reach -20°, it’s best to visit St. Petersburg in summer. The white nights happen late May to mid-July and with it comes a cultural festival.

Where to stay:

Comfortable: The Park Inn by Radisson: The rooms are plain but comfortable, the wi-fi works and the breakfast buffet is generous. From $225 per night in high season. Goncharnaya Street, Nevsky Prospect, St Petersburg.

Luxury: The W Hotel: This hip hotel is located steps from Nevsky Avenue and The Hermitage Museum. The rooftop terrace offers an enchanting view of St. Isaacs Cathedral. From $528 per night in high season. Voznesensky Prospect, St. Petersburg.

Where to eat:

Comfortable: miX in St. Petersburg: The menu is created by Michelin-starred chef Alain Ducasse. Good food and a relaxed atmosphere. Sample the vodka soufflé.

High-End: L’Europe Restaurant: Try the house specialty, the egg-in-egg caviar dish, and, since you’re here, allow the sommelier to pair your dishes with what he deems best. Aim to dine here on Thursday nights, when the restaurant features live entertainment by way of a string quartet, ballet and opera mini-performances.

You can’t leave without: Watching the raising of the bridges; eating borscht; and learning about the fascinating life of Peter the Great and his descendants.

Best thing about St. Petersburg: Really, just walking around this beautiful city is enough of an experience. Don’t try to cram too much in – make sure you leave enough time to just wander and get lost.

Worst thing about St. Petersburg: Russians’ aversion to smiling can be off-putting, so try not to let it get you down. Learn a few handy Russian phrases – “Excuse me”, “Hello” and “Thank you” should do it. They’ll appreciate the effort.

You should know:

Pre-purchase tickets online to The Hermitage and walk past the huge line.

Be aware of dodgy cab drivers – ask a local or concierge how much is reasonable to pay.

Be careful in metro stops as the automated ticket machines don’t have an English menu – it’s best to line up and ask for a ticket at the counter.

LEAVE YOUR COMMENT