Uncovering the many wonders of Yosemite and Sequoia

Sequoia National Park is known as ‘the land of giants’ for its huge sequoia trees. (Image: Getty/Brad Booth)

A tour of Yosemite and Sequoia traces the footsteps of the trailblazer behind the formation of California’s most iconic national parks.

In the dawn – while the stars still twinkle in the clear, cold Californian sky above – I re-read my safety tips, so that they might lodge in my subconscious. Hiking alone and jogging is not recommended.

Not here, in mountain lion habitat. But should I choose to – and if I encounter a mountain lion – the best thing to do is: stay calm. Don’t turn back. Appear as big as possible. If it acts aggressively, wave my arms. Throw a rock or shout. And here’s the doozy. If attacked, fight back.

A staff member on the early shift at my hotel adds his two cents’ worth as he pours my coffee. “There was a bear close by yesterday,” he says. “But they’re more scared of you than you are of them. Provided you don’t sneak up on them in the dark, of course.”

The park is home to black bears. (Image: Getty/anmuelle)

But then, you see, in 2024, Yosemite National Park received more than 4 million visitors – and 75 per cent of them arrived in the six months between May and October – so finding your own quiet place among this iconic landscape requires a whole new kind of trailblazing.

Yosemite National Park is characterised by looming granite cliffs. (Image: Getty/ Francesco Ricca Iacomino)

I’m here, at least, at the very end of prime visitation season in late October, on a tour that promises to show me as much about the pioneers behind Yosemite National Park as the park itself.

American-born tour operator and cruise line Tauck, which marks its 100th anniversary in 2025, sells its journey into California’s Yosemite and Sequoia national parks (and the Muir Woods National Monument) on the premise that it will go beyond the all-too-obvious show-and-tell to explain the story of the people behind the creation of these parks.

Yosemite National Park is an epic climbing locale. (Image: Josh Johnson)

Yosemite and Sequoia are especially significant, being as they are the birthplace of environmental activism as we know it today. And by ‘people’, they largely mean person. The tour is dubbed John Muir’s California.

The power of the Scottish-born American naturalist and author’s words to capture the ethereal quality of the Californian wilderness helped support the push for US Congress to establish these national parks in 1890.

“Keep close to Nature’s heart,” he wrote. “And break away … spend a week in the woods. Wash your spirit clean.” To be sure of it, Tauck has added a day; this tour lasts eight.

Yosemite will be the tour’s final destination. And while it’s what we’re all really here for, the first national park we visit – Sequoia – was as much of a catalyst for global environmentalism. The world’s second national park (after Yellowstone), it was formed a week before Yosemite.

The flat, dull and dusty drive across California’s Central Valley from our starting point in San Francisco amplifies the scale of the park. In 1872, mountaineer Clarence King described this place as, “A thousand upspringing spires pierce the sky in every direction.”

Yosemite’s jagged peaks. (Image: Brand USA VCA Road Trips)

The park’s highest peak – Mt Wilson – is the tallest mountain in America’s Lower 48 (states). A road cut into the western slopes of the Sierra Nevada mountains allows us access up and in; herds of mule deer slow our progress, but it’s the giant sequoias that stop us in our tracks.

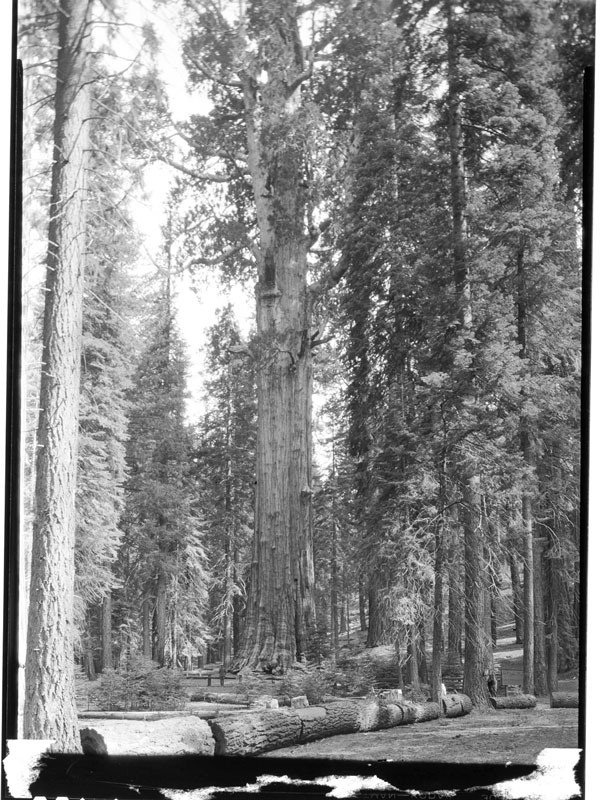

The world’s largest organisms by volume, there are trees more than 30 metres in circumference here – wide enough to block a six-lane freeway. And this is the only place on Earth they grow, some as tall as a 31-storey building.

Sequoia National Park is known as ‘the land of giants’ for its huge sequoia trees. (Image: Getty/Brad Booth)

There are 75 groves of giant sequoias in the park, but the Giant Forest grove is where the largest trees are. I’m in the middle of it, with the sweet butterscotch odour of the trees and the dank smell of the earth thick in the air.

General Sherman is the world’s biggest tree.

Most of the trees here are more than 2000 years old. But the granddaddy of them all, General Sherman, is older: more than 2500 years old. Its trunk clings to the planet like an enormous elephant foot. Considered the largest tree left on Earth, it takes me several minutes just to circumnavigate its base.

Coyotes roam the landscape. (Image: Getty/Spondylolithesis)

These giant sequoias were their very own environmental trendsetters. When word of the giants got out to America’s east coast and beyond to Europe, no one believed trees this huge existed in California.

But when proof came – and along with protestations against logging by writers such as John Muir who’d gone as far as to strap himself to trees in violent storms to provide dramatic excerpts in articles and books for his fellow Americans (“clinging with muscles firmly braced … the profound bass of the naked branches … booming like waterfalls”, he wrote) – the public demanded their protection.

Welcome to the Sequoia National Park. (Image: Getty/Ershov_Maks)

In 1890, Sequoia National Park became the first conservation area on Earth formed solely to protect a living organism.

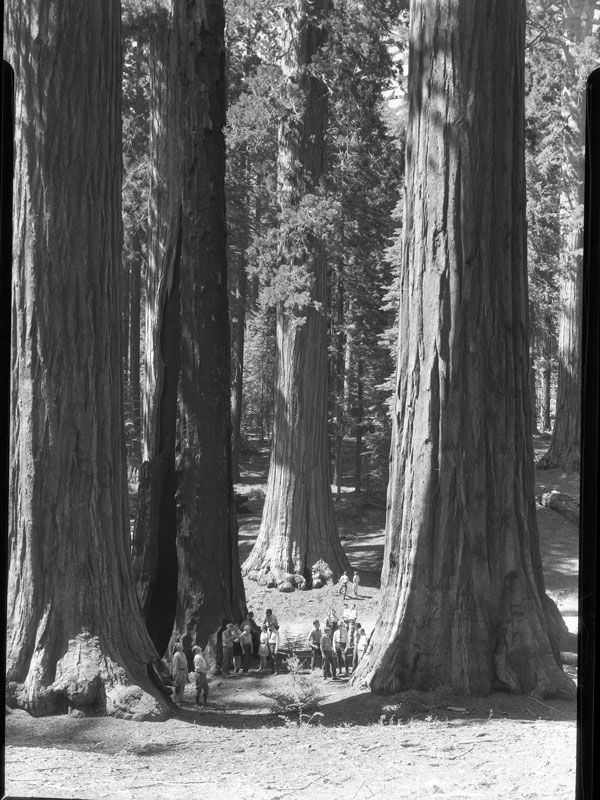

Understanding its role in the evolution of modern-day forest protection is a big part of the attraction to being here. The sheer freakish scale of these giants saved them (around 30 per cent of the giants were harvested before the national park was established). But until their size was confirmed, east coasters and Europeans referred to these trees as ‘the Californian hoax’.

A historic photo of a group among giant sequoias.

There are 80,000 of them in the park, but I can’t walk past a single one without stopping to stare, jaw agape. There are far fewer travellers in this park than Yosemite (around 1.2 million per annum), so it’s easier for me to disappear among the giants.

I stay in Wuksachi Lodge, deep in the wilderness. At night, when I can barely see trees, I take a blanket from my room and lie under a bulging sky with a billion stars. It’s a three-hour drive north to Yosemite from here. The road drops back down to the Central Valley, then spirals upwards, along the edge of the Sierra Nevada range.

Wuksachi Lodge is deep in Sequoia National Park.

I get my first view of the Yosemite Valley as we descend into it: including El Capitan, the world’s largest granite monolith and one of the planet’s most iconic climbing destinations; Yosemite Falls, at 739 metres, the highest waterfall in North America; and Half Dome, rising 1500 metres above the valley floor.

Bridalveil Falls in Yosemite Valley. (Image: Josh Johnson)

Muir, having walked 1600 kilometres to Florida from Kentucky, then hitching rides by boat to California, took two months to walk here from San Francisco in 1868 for the same view I have.

Half Dome in Yosemite National Park. (Image: Getty/yhelfman)

“The valley came suddenly into view throughout almost its whole extent,” he wrote. “The noble walls, sculptured into endless variety of domes and gables, spires and battlements and plain mural precipices, all a-tremble with the thunder tones of the falling water. The level bottom seemed to be dressed like a garden, sunny meadows … the river of Mercy sweeping in majesty through.”

But Muir’s Yosemite didn’t host 4.5 million visitors a year. Even now in late October, the crowds can be suffocating. But we’re staying in the middle of the park at the crown jewel of all America’s national park hotels.

The iconic Ahwahnee hotel.

Almost a century old, The Ahwahnee – listed on the National Register of Historic Places – has hosted US presidents and European royals. But what I like best is that it offers the best view of the orange-red alpenglow on Half Dome’s sheer rock face from its back lawn.

And that in the dawn – when I wake long before tourists gather en masse for their piece of the park – it’s a short walk in the dark along hiking trails to historic stone bridges over narrow rivers where water rushes through cascades of shiny, smooth pebbles. And there’s nothing at all to hear but the sound of it.

And that I can walk then, as the sky slowly lightens, beside huge green meadows, surrounded on all sides by the all-too-famous features of the park; and yet I don’t have to share it.

Yosemite was declared a national park just after Sequoia in 1890. (Image: Josh Johnson)

The trailblazers of this park inspire these lonely explorations I take each morning, before the guided tours begin. “Only by going alone in silence, without baggage, can one truly get into the heart of the wilderness,” Muir wrote.

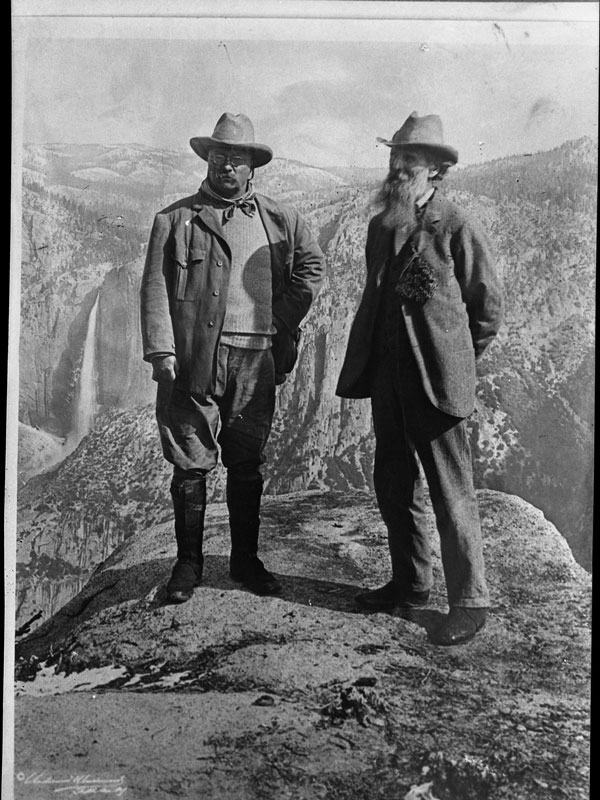

John Muir and Teddy Roosevelt at Glacier Point.

In 1903, Muir took President Theodore Roosevelt on a three-day camping tour across Yosemite. So impressed by the silence – and the beauty of what I’m seeing a century-or-so later – Roosevelt doubled the number of US national parks; by the end of his presidency, he’d set aside 93 million hectares of wilderness for protection.

The history of the country’s hallowed national parks is marred by the displacement and dispossession of its Native American peoples. Muir himself has been accused in recent years of disseminating derogatory comments about California’s Indigenous population.

American magazine The Atlantic requests that we: “Don’t cancel him – but don’t excuse him either”. And the appointment in 2022 of the National Park Service’s first Native American director, Charles ‘Chuck’ F. Sams III, who aims to increase tribal nations’ role in managing public lands, signals progress.

But it’s undeniable that Muir is a critical figure in environmental conservation, who introduced the concept of beauty in nature to America, and then to the world. It must have stuck: 4 million or so people a year sure aren’t here for the cuisine.

“Thousands of tired, nerve-shaken, over-civilised people are beginning to find out that going to the mountains is going home,” Muir wrote.

The early morning sunlight sieves through the trees, and squirrels and chipmunks bolt among the undergrowth. The sky looks so big and so blue that I wonder if California remembers how to produce a cloud. And I feel a real sense of calm in an anxious world.

Keep your eye out for bears. (Image: Getty/brentawp)

A traveller’s checklist

Getting there

Air New Zealand flies daily to San Francisco via Auckland from Australia’s east coast.

Playing there

Tauck’s eight-day, seven-night Yosemite & Sequoia, John Muir’s California tour runs from May to June and August to October. It includes nights in both national parks and two nights in San Francisco, with an excursion to Muir Woods National Monument. Prices start from $10,290 per person, including accommodation, all touring, most meals and airport transfers. Exclusive to Tauck, this tour features vignettes by filmmakers Ken Burns and Dayton Duncan that tell the stories of the national parks.

A tour group in Yosemite. (Image: Mason Trinca)

LEAVE YOUR COMMENT