A four-day hike along The Lighthouse Way, Spain

Walking along Galicia’s Lighthouse Way in northern Spain, we follow a new path to the ‘end of the world’.

My fingers are stained tempranillo red from picking the blackberries that grow wild on Galicia’s coast. The small inky fruits pulse with sweetness, rendered tender and delicious by the Spanish sun. The berries are a welcome snack in the absence of lunch – to my dismay, I’d mistimed my arrival to the only restaurant around for miles, finding it shuttered and closed for siesta.

The trail steers me and my partner inland past a lonely farmhouse. A grey cat naps on the sun-lit porch and a mighty pear tree casts dappled shade onto the garden, the branches ripe and heavy with fruit. A farmer sits a few yards away, scrubbing potatoes with his wife and young son.

A farmer watches his cattle. (Image: Jeremy Zafiropoulos)

Day one

The conditioning of city life makes it feel somehow taboo to ask this stranger if I can have a pear. But I’m reminded that I am on a pilgrimage, and this is what pilgrims have done throughout the centuries. In fractured Spanish, we call out to the farmer: “Good day sir. We are travellers. We have been walking all day and are very hungry. Please may we take a piece of fruit from your tree? The farmer disappears momentarily into his house and reappears with a bag, handing it to us and motioning to fill it. “Toma, toma,” he says. “It’s a shame the peaches aren’t ripe, too.”

Abundant fruit trees dot the trail in summer. (Image: Jeremy Zafiropoulos)

I’m on the first of a four-day hike along The Lighthouse Way in Spain’s north-west, a trail that links Galicia’s agrarian and fishing villages via the rugged cliffs and secluded beaches of the Costa da Morte (literally, ‘Coast of Death’).

On account of the shipwrecks that have occurred off this treacherous stretch of coast, several lighthouses were erected here in the 19th and 20th centuries, and many are still in use today.

The Costa da Morte is a beautiful yet treacherous stretch of coast. (Image: Jeremy Zafiropoulos)

The scenes along The Lighthouse Way invoke a bygone era through images that recur like motifs. Mud-speckled tractors. Wheelbarrows overflowing with earth-dusted produce.

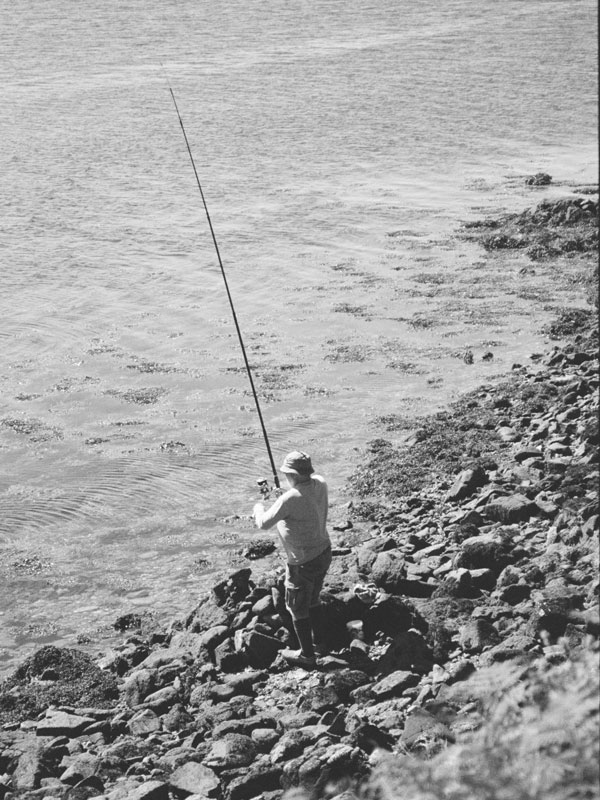

Salt-bearded fishermen biding by the water’s edge, their lines cast into the glimmering depths. Elderly abuelos sitting in front of their homes, surveying the cobbled streets as the sun burns a sweeping arc across the pale blue sky. “Buenos días,” they call out as we pass them by. “Buenos días,” I always echo back.

A fisherman by the water’s edge. (Image: Jeremy Zafiropoulos)

Cape Finisterre

Cape Finisterre is a primordial place with an eternally mystic pull; before the Romans, it was a ritual site of Celtic sun worship.

We start the trail in the fishing town of Camariñas, leaving behind the technicolour buildings and lilting croon of seagulls as we make tracks to our ultimate destination, Cape Finisterre. Finisterre comes from the Latin finis terrae, meaning ‘end of the Earth’.

The trail links a fishing village with colourful houses. (Image: Jeremy Zafiropoulos)

In Roman times, this was believed to be the farthest point of the world, the final frontier before the vast unknown. It’s a primordial place with an eternally mystic pull; before the Romans, it was a ritual site of Celtic sun worship. Since the Middle Ages, the site has received thousands of pilgrims arriving off the back of the Camino de Santiago. Finisterre lies less than 100 kilometres west of Santiago de Compostela, the hallowed end to the historic pilgrimage. From here, many pilgrims continued their journey to the edge of the world, lured by the mythology and ancient secrets of the Cape.

Believed to be the end of the world by the Romans. (Image: Jeremy Zafiropoulos)

An epic trail

But unlike the well-trodden Camino de Santiago, which beckoned half a million people to its trails last year, The Lighthouse Way is an unsung, largely undiscovered path to the world’s end. A decade ago, a few Galician friends hatched a plan to connect all of the faros (lighthouses) via a trail between the ancient port of Malpica and Cape Finisterre. Much of the groundwork was already laid out – thanks to unofficial paths trampled by the boots of local fishermen and percebeiros (barnacle gatherers) over the years. But aside from a few anglers ambling along, we hardly share the trail with anyone else.

The trails are largely unfrequented, unlike the nearby Camino de Santiago. (Image: Jeremy Zafiropoulos)

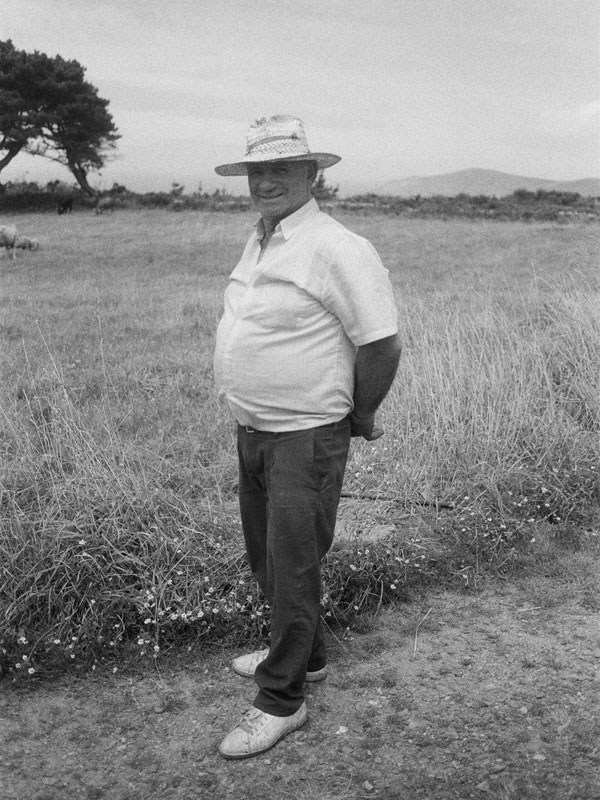

On a particularly remote stretch, we’ve gone hours without seeing another soul when I spot a little straw hat poking out of the long grass. The wearer is a cattle farmer, sitting cross-legged on the earth as he watches his herd graze. We stop to speak, doing our respective best to breach the language barrier. “I’ve been sitting here all day,” he says. His kind eyes are milky blue, his skin weathered by the sun. There’s a section of trail ahead that’s very steep, he warns us, “but the views are beautiful ”.

The Lighthouse Way was created with the help of farmers and fishermen. (Image: Jeremy Zafiropoulos)

Days two and three

Over the next days, we follow the undulating coast, rising and falling like the waves rolling in from the Atlantic. We trace turquoise inlets fringed by purple bell heather and golden buttercups. We take our sweet time, stripping down to our bathers to cool off at deserted beaches, the cool water sparkling in the sun like a vast, pale-blue jewel.

Trace the glittering inlets of the Atlantic Coast. (Image: Jeremy Zafiropoulos)

Lunch

Missing lunch is a mistake we make sure not to repeat. Calling in at coastal village restaurants along the way, we soon begin to uncover a pattern: the more outdated the decor, the better the food.

Enjoy local seafood and wine at the end of each day. (Image: Hotel O Semaforo)

Seafood is the region’s speciality, and we sample the gamut. Crispy octopus croquettes and fried calamari. Razor clams and orange mussels cooked in wine. And best of all, buttery zamburiñas (scallops), so fresh I feel the Atlantic echo on my palate when I bite into the succulent white flesh. Meals are always washed down with an ice-cold cerveza.

Seafood is a Galician speciality. (Image: Jeremy Zafiropoulos)

Sometimes, lunch is just a simple meal of crusty bread, cheese and jamón. In the general store of a rural village, I buy sandwich ingredients and cans of Estrella beer from a little girl who doesn’t look to be more than seven or eight. Her arms barely reach over the counter as she passes me my change.

Dotted along the harbour of Muxía are coastal village restaurants. (Image: Jeremy Zafiropoulos)

Where we stayed

Accommodation is a series of rustic B&Bs with cool stone walls and hydrangeas blooming in the garden. One night, when our lodgings are particularly remote, dinner is prepared by the owner who cooks juicy, tender fillets of hake served on a bed of sautéed garden vegetables. A bottle of local albariño wine accompanies – a refreshingly light white varietal with fruity, citrus notes.

Stay at charming B&B accommodation along the way. (Image: Jeremy Zafiropoulos)

Galicia feels distinct from the rest of Spain. And not just for the mysterious stilted hórreos (old Galician granaries) that dot the landscape. Whereas the rest of the Iberian Peninsula is hot and honey-hued, here feels soft and silver-toned; as if I’m perpetually looking through a hazy film of sea mist. Even the sun seems tinged a more pallid shade.

Rustic stone houses are a characteristic of rural Spain. (Image: Jeremy Zafiropoulos)

It makes sense – the Gallaeci (Spanish Celts) believed that the sun died when it set here. They were animists, imbuing soul and spirit into nature and all its phenomena. That heritage still lingers today, evidenced by curious Celtic spiral symbols that can be spotted around the region, painted or inscribed onto buildings like runes.

Hórreos (stilted granaries) are common sights in the countryside. (Image: Jeremy Zafiropoulos)

Day four

On the final day, the Costa da Morte reveals the tempestuous nature she’s named for. The wind whips my hair around as I manoeuvre along a narrow path that hugs the edge of a cliff. There’s a steep drop to the roaring ocean below, which churns and batters against lichen-covered rocks. At last, the trail guides us back to the safety of the main road. Hungry and weary, my partner scales a crumbling stone wall on the wayside to reach the bough of a wild apple tree.

Our yield is tart and delicious, and we crunch on the fruit as the track steers us into an aromatic pine forest, the woody scent carried by a rising mist. When we emerge onto a cliff, the mist has thickened to a white wall. It feels as though I’m suspended in a liminal space, crossing a threshold to somewhere mystic and unknown. Cape Finisterre lies just beyond. I can’t see it through the fog, but I feel its magnetism.

A fishing village sits in the afternoon sun. (Image: Jeremy Zafiropoulos)

The sky is smudged molasses black and sheets of rain are descending when we reach our lodgings at Hotel O Semáforo, in the converted Finisterre Lighthouse perched on the edge of the Cape. But I awake in the morning to find Costa da Morte quelled and calm. Foamy waves lap the cliffs. Heather-purple clouds mottle across the sky. I teeter on the rim of the Earth as I watch the sun resurrect, illuminating the land that has nourished us wholly over the past days. Not just with the ripe abundance of her earth and sea. But with her vast, untamed beauty that will stay with me long after my blisters heal.

Hotel O Semáforo sits within the Lighthouse at Cape Finisterre. (Image: Getty/DrCooke)

Getting there

You can fly into Galicia via airports in Santiago de Compostela and A Coruña. Or take the fast train to Santiago de Compostela from Madrid, which takes about three-and-a-half hours.

Walking there

Walk The Lighthouse Way with On Foot Holidays, a self-guided walking tour company that organises itineraries across Europe. Accommodation is booked on your behalf and you’ll be provided with a detailed map and walking instructions in advance. You’ll also be provided with a local contact via WhatsApp, who can help out in case of emergency or simply provide local tips and restaurant recommendations.

The route is adjustable for different fitness levels by local taxi if you wish to shorten the hike. Your local contact can assist in organising this. Each day, all you need to do is pack a day bag, leave your luggage at reception and head out. The Lighthouse Way is available as a five-, seven- and 10-night experience.

LEAVE YOUR COMMENT