The church of Saint Ignatius in Rome (or San Ignazio) has become a viral selfie location. Tourists have been queuing out the doors for a chance to take a selfie in a mirror that reflects the church’s richly painted ceiling.

The vault was painted by the artist Andrea Pozzo between 1688 and 1694. In the centre we can see Saint Ignatius of Loyola (1491–1556), the founder of the Jesuit order. He is ascending through the clouds to heaven while a divine light pours into him and through him to representations of the four continents of the world, an allegory of the missionary work of the Jesuit order.

The real fascination of the painting is the optical illusion Pozzo created, which is probably also why it is gaining fans as an Instagram backdrop.

When you look up at the painting it seems the real architecture of the nave continue upwards to an impossible height and the roof has lifted off entirely.

Figures of angels dangle their legs from cloud, saints gaze down towards us or look towards heaven, putti (baby angels) hold symbolic objects and peek from beneath voluminous robes, while animals charge out from behind the architecture.

Even with the most critical eye it can seem impossible to tell where the real church ends and the illusion begins.

@jennaliston The Cathedral of St. Ignatius, Rome is unreal. #rome #travel #views #cathedral ♬ original sound – xxtristanxo

An ‘illusionistic’ ceiling painting

Pozzo’s masterpiece marks a significant moment in the history of illusionistic painting in Europe.

Since the 15th century, artists and architects had been interested in refining the use of a technique called “linear perspective” that allowed them to depict three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional surface. Anyone who has tried their hand at drawing lessons has probably had a go at depicting this kind of perspective.

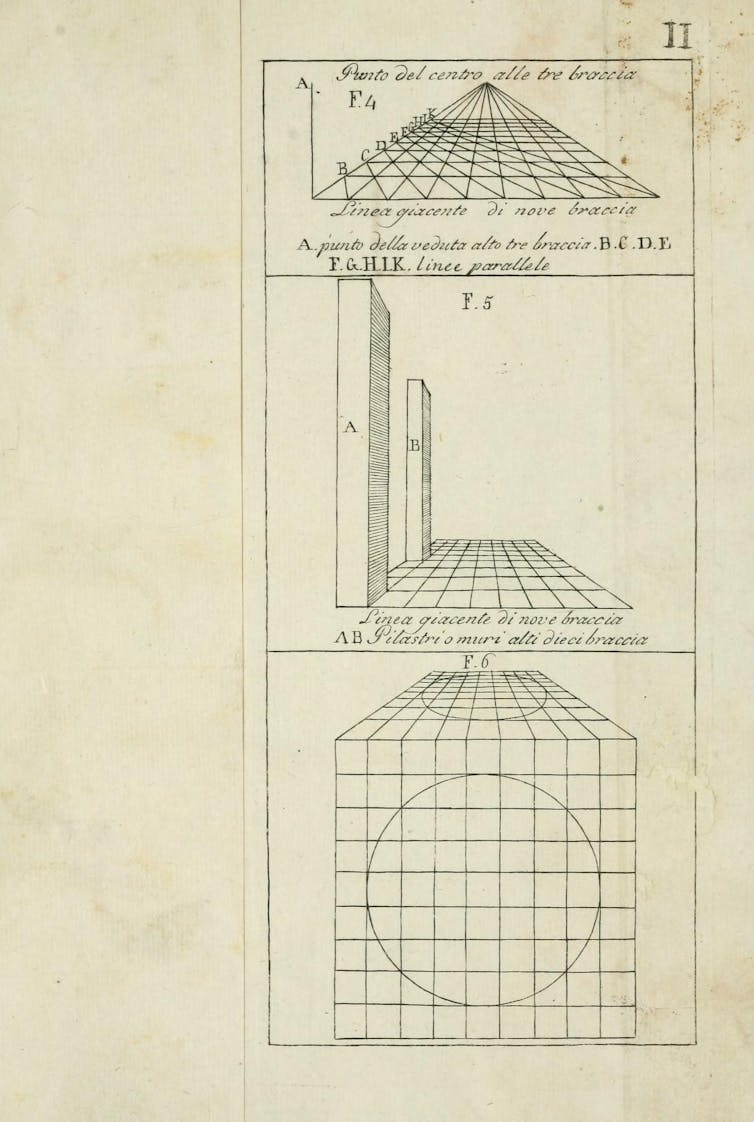

A common exercise, found in a 15th-century book by the architect Leon Battista Alberti, shows the example of drawing straight lines that converge at a single point to create the illusion of depth.

Images of linear perspective from Leon Battista Alberti’s On Painting and On Sculpture, from a version published in 1804. Getty Research Institute via archive.org

Pozzo was one of the leading artists in the 17th century for this style of painting. He wrote a book, Rules and Examples of Perspective, explaining how he created these optical illusions using perspective.

For the ceiling of Saint Ignatius he first created a drawing on paper divided into squares. A grid was then suspended on the ceiling by attaching pieces of string to the cornice (the moulding between the wall and ceiling).

A central point on the floor (where the selfie mirror is) was chosen as the central viewing point and the design was copied line by line onto the ceiling. This was challenging as the ceiling is not flat, but curved.

If you could view it up close you would see that the figures and lines of architecture are distorted, stretched, curved and foreshortened, but when viewed from the central spot on the floor it creates a seamless illusion.

The science of vision

The fascination with illusionistic ceiling paintings in this period in Europe was in part a response to new scientific ideas about optics – the study of the properties of light.

Painting was regarded as an art that had its foundations in scientific reasoning. The best painters understood how shadows and light worked, understood colour theories and studied perspective and anatomy.

In 1604 the astronomer, mathematician and natural philosopher Johannes Kepler published a text proposing that vision was based on light passing through the cornea, pupil and lens to produce an image on the retina.

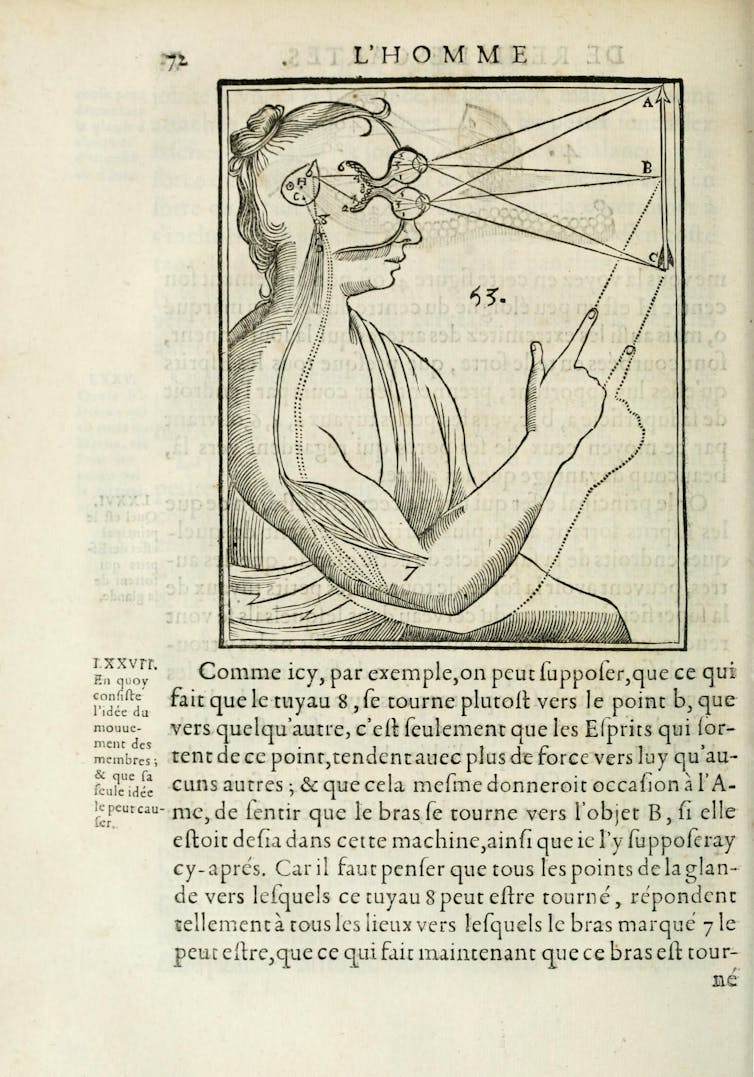

The philosopher Rene Descartes then proposed in two works, Dioptrique (Optics), published in 1637, and L’Homme (Treatise on Man), published posthumously in 1662, that these images were conducted to the brain – the idea of sensory projection.

Art played an important role in helping people conceptualise these new ideas. Both Descartes and Kepler used the metaphor of “painting” to describe how light created an image on the retina.

In the illustrations created for Descartes’ L’Homme we also see how theories about seeing were illustrated using geometry and linear perspective.

Engraving showing a demonstration of Descartes’ theories of vision from A Treatise on Man, this version was published in Paris in 1677. Archive.org

This new understanding of vision also led to the realisation the eye could be manipulated. Optical illusions in art prompted delight and anxiety about whether the eye could be trusted. They also prompted deeper reflection about the nature of truth and existence of god.

A theatre of religious visions

Illusionistic paintings in churches also had a religious purpose.

The Jesuits regarded performance and spectacle as a central part of their mission to educate and inspire religious devotion. Philosophers like Descartes believed that the experience of wonder prompted an emotional response that could transform the mind.

It is likely Pozzo was inspired by these popular ideas about wonder.

Visitors in the 17th century experienced the sense of amazement, as we still do, but the idea was this moment of wonder would translate into stronger religious faith.

These paintings helped to make abstract concepts – like religious faith and ascending to heaven – more real and tangible.

View this post on Instagram

Why does a 350-year-old painting still hold such an attraction for modern visitors? For some, the religious message is still significant.

For many others it is the illusion that draws us in. We know what we see is not real, yet our brains register it as such. The visual dissonance delights and intrigues us.

And still for many it is just a popular Instagram or TikTok backdrop. But, hopefully, it is also a reminder that, in a world flooded with constructed and fake images, the eye is easily fooled.

Katrina Grant, Research Associate, Power Institute for Arts and Visual Culture, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

LEAVE YOUR COMMENT