Discover the French Riviera by rail

The French Riviera is an enduring muse that owes much of its prowess to the iconic trains that carried wealthy socialites and artists to its cerulean shores in the 20th Century. We hop onboard to relive the romance of the railway en route to the Riviera.

My glass of Bordeaux red catches pale ribbons of sunlight streaming through the window, refracting them onto the dining table where they land like scattered rubies. I sip the wine – bold and brassy with notes of blackcurrant – beneath a ceiling painted with elaborate frescoes.

Statues of golden cherubs and bare-chested mermaids preside over me from their fixtures above vaulted doorways. No wall space is left empty – what isn’t blanketed by mural or sculpture is resplendent in ornate gold detailing and Rococo-style motifs. But this is no aristocrat’s palace. This is a train station.

The Blue Train experience

One might be surprised to find one of Paris’s most esteemed eateries tucked inside Gare de Lyon, a stale croissant’s throw from the usual train station fare of lacklustre coffee and shrink-wrapped sandwiches. But Le Train Bleu restaurant is a two-Michelin-starred fine-dining affair, named for The Blue Train, the now-defunct luxury locomotive that carried high society to the French Riviera throughout the 20th century.

Le Train Bleu is located in Gare de Lyon train station. (Image: Roussel Bernard/Alamy Stock Photo)

Established in 1901, Le Train Bleu restaurant is a monument historique and a shining example of Belle Époque architecture. In the golden age of rail travel, wealthy passengers would have begun their journey as I am now, wining and dining beneath a canopy of fine art, waiting to board The Blue Train bound for the cerulean shores of the Côte d’Azur.

Le Train Bleu is resplendent with breathtaking paintings. (Image: Le Photographe Du Dimanche)

The vivid paintings that blanket the restaurant are what’s known as vedute (meaning ‘views’ in Italian), a style of art that depicts highly detailed landscapes. Each veduta in the dining hall illustrates scenes from stations serviced by the old railway line. From my table, I can see the gleaming harbour of Marseille. Pine trees fringing the sea in Villefranche. Waves lapping the rugged, coastal cliffs of Monaco. For passengers dining here throughout the ages, these vedute whetted the appetite for travel, serving as a taste of what was to come. Much like the ramekin of watermelon amuse-bouche a waiter has just placed in front of me.

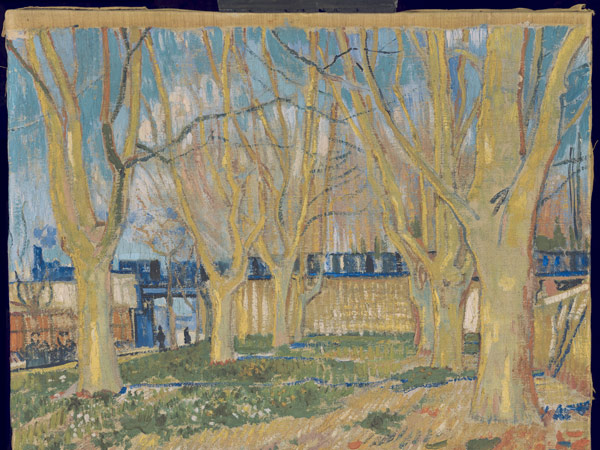

The Blue Train painted by Vincent Van Gogh in 1888.

An entrée of Kingfish carpaccio follows, encapsulating the taste of summer with satiny sheets of sashimi doused in a citrus vinaigrette. For mains, velvety dauphinoise potatoes are a fine accompaniment to succulent roast lamb (the restaurant’s signature dish), sliced at our table from an antique silver carving trolley. One could easily forgive a delayed train, given the chance to linger here just a while longer. But alas, mine is running to schedule – no time for dessert. I make it to the platform with just a minute to spare.

Journey through the heart of France

The train hurtles due south, barrelling through the heart of France. We pass through the flatlands of the north, with its rickety old châteaus amid pin-straight grids of vines. Mountains rise as we pass the nation’s navel. Then, the gleaming waters of the Mediterranean are upon us, billowing out like an endless blue silk scarf.

The high-speed commuter trains may not have the opulent interiors of The Blue Train, but the scenes of the countryside are an inalienable luxury. Upon reaching Marseille, the locomotive drops down a gear and meanders along the coast, calling in at the main resort towns of the Riviera. Through the frame of the window, the painterly scenes from the vedute in the restaurant are fully realised.

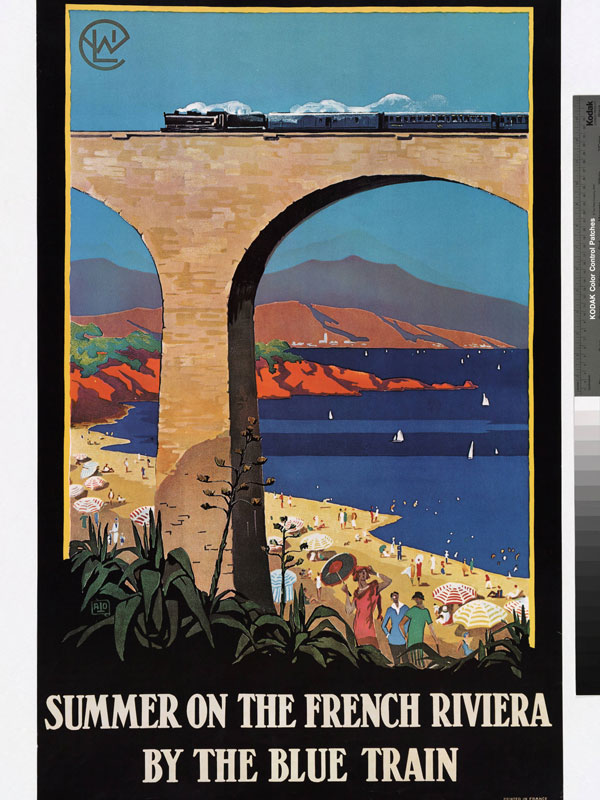

The Blue Train was an iconic locomotive that helped launch the Riviera to star status.

There’s a certain image that springs to mind when one thinks of a European summer vacation. Tanning in designer swimwear by day. Imbibing cultural cachet and cocktails by night. The Euro beach holiday is relaxed, but always glamorous. This vision is an enduring one, and it owes much to the rise of the French Riviera.

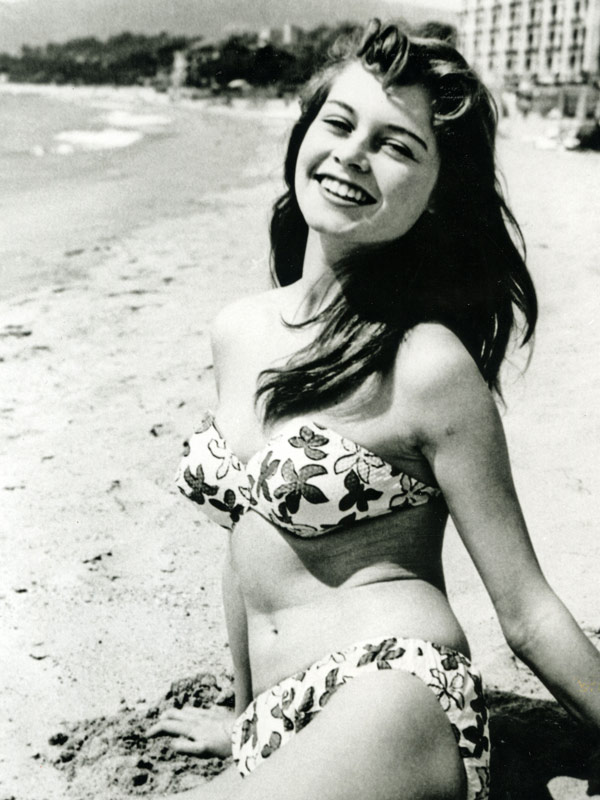

The bikini was invented, unveiled and popularised right here – most notably by Brigitte Bardot – who drew mass media attention after being photographed sunbathing in one during Cannes Film Festival in 1953. Tanning also became in vogue after Coco Chanel returned from Cannes sporting a bronzage. (Chanel was one of The Blue Train’s early passengers. She also designed the costumes for the Ballets Russes production of Le Train Bleu, a ballet inspired by and named after the famous train).

Brigitte Bardot popularised the bikini on the beaches of Cannes in 1953. (Image: Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy Stock Photo)

Fuelled by the artists, intellectuals, socialites and belle monde filtering in via the railway, the region became a lightning rod for arts, culture, glamour and hedonism – all alchemising to create the mythos of the Riviera. Just like a young Brigitte Bardot making her debut at Cannes Film Festival, a star was born.

Beyond the image of the Riviera is the idea of it. It’s synonymous with style and sophistication, and above all, a sense of escapism. It’s a conception that’s been canonised by countless movies and mood boards, so much so, that I half-expect my visit to play out like a sequence from a French New Wave film. But when I alight the train at Antibes, all preconceptions fall away. The Côte d’Azur is no longer an image or an idea. It’s tactile. Corporeal. It’s a sensory experience that envelops me entirely.

The alluring colours of the Riviera. (Image: Jeremy Zafiropoulos)

A secret island off of Cannes

The air is perfumed by the warm scent of the pine trees and soft smell of jasmine, lulled in by the salty sea breeze. In the hills above me, the medieval town of Grasse harnesses the abundance of flowers that grow here in its countless perfumeries. I purchase a small vial of Narcisse fragrance, a flower known colloquially as poet’s daffodil, and to perfumers as ‘white gold’. Even now, when I spray the delicate scent, the soft, luminous atmosphere of the Côte d’Azur comes rushing back.

Jewel-toned waters off Île Saint-Honorat. (Image: Jeremy Zafiropoulos)

The Riviera is the sort of place you go to see and be seen. But I decide to swap the high society hang-out spots for a slice of solace. Île Saint-Honorat – an island solely inhabited by a cloister of Cistercian monks – is just a 15-minute ferry ride from Cannes. But I’m not here to practice asceticism. I sample glasses of fruity syrah and oaky chardonnay in the monastery’s sun-dappled vineyard, which has been tended to by monks since the Middle Ages. The rest of the day is spent swimming in the jewel-toned waters off the island, which I have all to myself, save for a few yachts bobbing in the distance.

The Cote d’Azur lives up to its name. (Image: Unsplash/Daniel Stiel)

Ancient Antibes

Back in Antibes, I end the evening with a cocktail at Fitzgerald bar at Hotel Belles Rives. I’m sitting outside, overlooking the hotel’s private beach and watching the sea slowly turn from sapphire to onyx as night falls. The hotel is the former villa of F. Scott Fitzgerald and his wife, Zelda (Fitzgerald was another early passenger of The Blue Train).

The American writer, like so many artists past and present, relocated to the Côte d’Azur in search of inspiration for his work. He found it. “We were going to the Old World to find a new rhythm to our lives,” Fitzgerald wrote of the move. “With a true conviction that we had left our old selves behind forever.” Evidently, the mythology of the French Riviera was as alive then as it is today.

Fitzgerald Bar in Hotel Belles Rives, the former home of the American writer.

A traveller’s checklist

Getting there

There are direct high-speed trains to the French Riviera departing from Paris Gare de Lyon. It takes about five hours to reach Cannes.

Relive the romance of the railways with a Eurail pass – you’ll get unlimited rail travel for each of your selected days – perfect for visiting the resort towns scattered along the coast or exploring further afield.

Travel to the Riviera onboard a high speed train. (Image: Panther Media GMBH/Alamy Stock Photo)

Staying there

Absorb some of the Riviera’s je ne sais quoi at F. Scott Fitzgerald’s former seaside villa, the luxurious five-star Hotel Belles Rives. However, those who aren’t guests can enjoy a cocktail at Fitzgerald Bar or reserve a daybed on the hotel’s private beach.

The private beach at Belles Rives. (Image: Daniel Stiel/Unsplash)

Eating there

Le Train Bleu restaurant in Gare de Lyon is an unmissable dining experience. It’s the one time you won’t mind getting to a station early.

In the Riviera, don’t overlook the understated snack shacks for a casual bite. The hearty country-style sandwiches at Chez Josy and La Crique are to die for.

Grab a pre-journey bite to eat. (Image: Le Photographe Du Dimanche)

More ways to explore Europe by rail

From run-of-the-mill commuter trains to luxury locomotives, these iconic railways illustrate that the joy is in the journey, not just the destination.

There’s world-class service onboard the fabled Venice Simplon-Orient-Express.

Paris to Portofino, The Venice Simplon-Orient-Express

The Italian Riviera is the chic little sister of the French Riviera – and every bit as breathtaking. Watch the vistas unfold onboard the luxurious Venice Simplon-Orient-Express, a Belmond train. Outfitted in Art Deco decor, the resplendent interiors recall the romance of a golden age of rail travel. In June, the luxury locomotive will depart from its usual itinerary to journey from Paris to Portofino, the train’s first visit to the Italian resort town in 42 years. Talk about arriving in style.

Spacious suites onboard the Venice Simplon-Orient-Express evoke the golden age of rail travel.

The Glacier Express, Switzerland

The Glacier Express has been called the ‘slowest express train in the world’. However, the laid-back pace works in passengers’ favour, allowing for lingering views of the Swiss Alps as the train glides between St Moritz and Zermatt. Almost as impressive as the scenery is the feat of engineering in constructing the railway – you’ll pass over some 291 bridges and through some 91 tunnels in the course of this 300-kilometre epic journey across Switzerland.

The Glacier Express takes in the Swiss Alps. (Image: Stock87 via Getty Images)

Linha Do Douro, Portugal

A train journey on the Linha do Douro is a venture through the heart of Portugal’s wine country. From Porto, the train traces both the Douro valley and river, cleaving some of the continent’s most picturesque scenery for 200 kilometres, until it reaches the Spanish border. The railway tracks are fringed by bucolic scenes and terraced vineyards. Don’t worry, there are plenty of stops along the way, so you can get off to sample local wines and ports.

Flåm Railway, Norway

You’ve heard of slow travel, but what about slow television? The Flåm Railway is so beautiful that all seven hours of the train journey from Bergen to Oslo were broadcast live without interruption. This train journey is Europe’s highest railway, taking in all that Scandinavia is famed for: fjords, mountains and majestic, misty waterfalls.

LEAVE YOUR COMMENT