Why the Frida Kahlo Museum definitely lives up to the hype

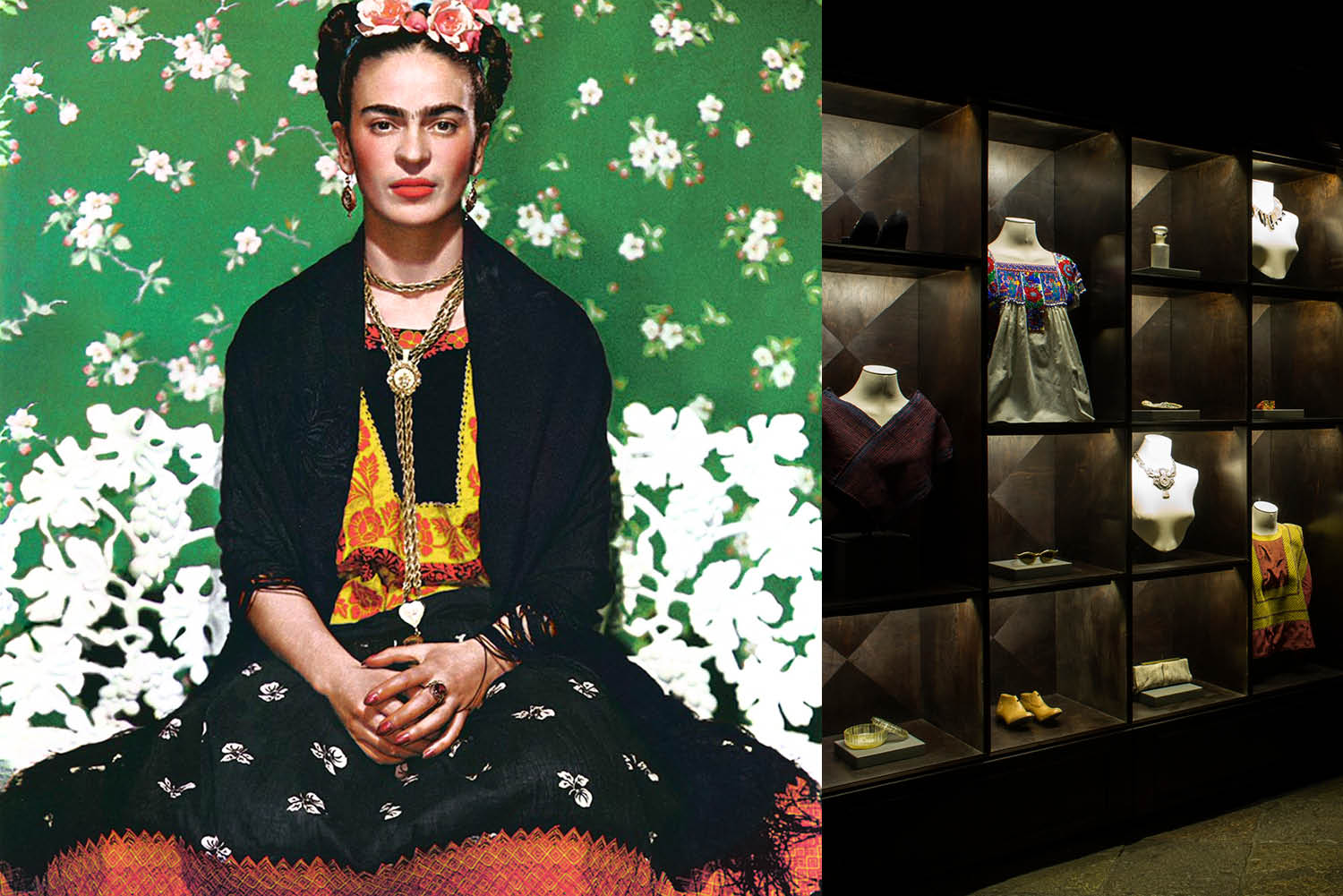

Frida Kahlo in trademark dress (photo: Nikolas Muray Archive).

An exhibition of Frida Kahlo’s colourful and confronting wardrobe reveals how avant-garde the artist really was.

A tomato-red boot, embroidered with Chinese motifs, sits on a wooden shelf at the Museo Frida Kahlo (Frida Kahlo Museum) in Mexico City. Kahlo designed the lace-up boot to fit her prosthetic leg. Now it is part of an exhibition, Appearances Can Be Deceiving: Frida Kahlo’s Wardrobe, on display in the exhibit rooms joined to La Casa Azul (The Blue House) museum.

La Casa Azul

The Mexican artist and style icon was born inside these cobalt-blue walls in 1907 and died here just 47 years later. The contents of Kahlo’s wardrobe are as unique and modern as the woman and her paintings. Who else would have owned a pair of earrings given to her by Pablo Picasso, or a chest cast painted with a hammer and sickle? “Each of these items reveals the creative heart of a woman with unlimited imagination,” says museum guide Jocelyn Pegoreti.

The location

The Frida Kahlo Museum is in Coyocoán, a leafy suburb a half-hour drive south of the heaving city centre. This was once a neighbourhood of intellectuals, home to Kahlo’s family as well as Diego Rivera, the Mexican muralist who eventually became her husband. The Soviet revolutionary Leon Trotsky, an associate of the couple who Kahlo had an affair with, was living in Coyocoán when he was assassinated in 1940.

Despite all its political, artistic and literary history, Coyocoán feels like a village. The urban sprawl of Mexico City only caught up with it in the mid-20th century. It’s easy to imagine Kahlo, with her trademark monobrow and red lipstick, walking the cafe-lined streets in a flowing skirt or a huipil (cotton tunic) decorated with lace and satin ribbons.

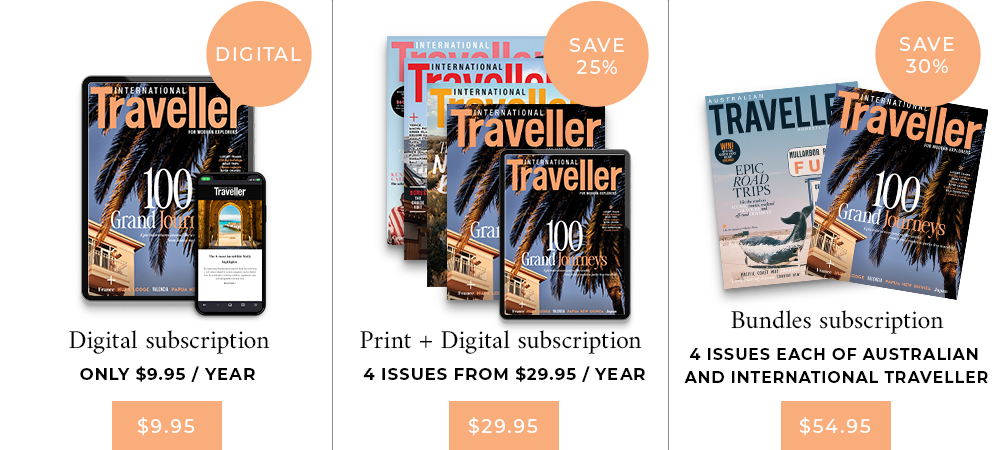

Frida Khalo’s work on display .

Frida Kahlo’s clothes

Given how important her clothes were in creating the cult of Kahlo, the fact that her clothing and personal effects remained in storage for more than 50 years, first at the specific request of Rivera and later by their patron and friend Dolores Olmedo, is remarkable. In April 2004 about 300 items – garments, jewellery, medicines and orthopedic devices – were discovered in the white-tiled bathroom on the upper level of La Casa Azul.

Room one of the exhibition

The lace-up boot designed by Kahlo to fit her prosthetic leg (photo: Leah McLennan).

The first room of the exhibition features the ‘disability wall’. Here, all of Kahlo’s corsets, crutches and prosthetic limbs hang on a tiled wall – a reminder of the bathroom in which the objects were found. These items tell of the painter’s lifelong battle with pain; at the age of six Kahlo was stricken with polio, which left one leg permanently thinner and weaker than the other. Then when she was 18 she was nearly killed in a trolley bus accident. A metal handrail pierced her body, entering at the shoulder and exiting at the hip, shattering her shoulder, leg, pelvis and ribs. Her womb was also damaged. Kahlo designed the red-booted prosthetic after her right leg was amputated in 1953.

Room two of the exhibition

Collection of colourful dresses made by the artist.

The exhibition’s second room is much more cheerful. Nine colourful dresses, all artfully lit, shine out from behind a glass wall. Each outfit includes the three main elements of traditional Tehuana costume – floral headpiece, flowing dress and square-cut tunic. The Tehuana dress originated in Oaxaca, a south-eastern region of Mexico that has a matriarchal society. Kahlo’s mother, Matilde, came from Oaxaca. (Kahlo’s father, Guillermo, was a German immigrant.) Kahlo wore these dresses because they symbolised both independent women and indigenous Mexican culture. They were also intensely practical: “I must have full skirts and long, now that my sick leg is so ugly,” Kahlo once said.

In the same room as her dresses is the drawing Appearances Can Be Deceiving, which inspired the show’s name. It was also discovered in the bathroom, and features Kahlo wearing only a plaster corset and a transparent Tehuana dress. Blue butterflies are drawn on her left leg. It brings to mind another Kahlo quote: “Feet, what do I need them for if I have wings to fly?”

The bedroom

As you wander through La Casa Azul it’s impossible not to linger in the bedroom. Kahlo had a mirror suspended from her four-poster canopy bed so she could paint self-portraits while lying down to relieve the pain she experienced for the rest of her life as a result of her injuries.

Kahlo’s death mask is laid out on the bed. Nearby is the urn containing her ashes, and a pillow embroidered with the words: “Do not forget me, my love.”

The line of adoring fans that I pass stretching down Londres Street as I leave, all waiting to enter her deep blue house, bears testament to the fact that she has not been forgotten, and with a tribute as compelling at La Casa Azul, she is not likely to be in the future.

LEAVE YOUR COMMENT