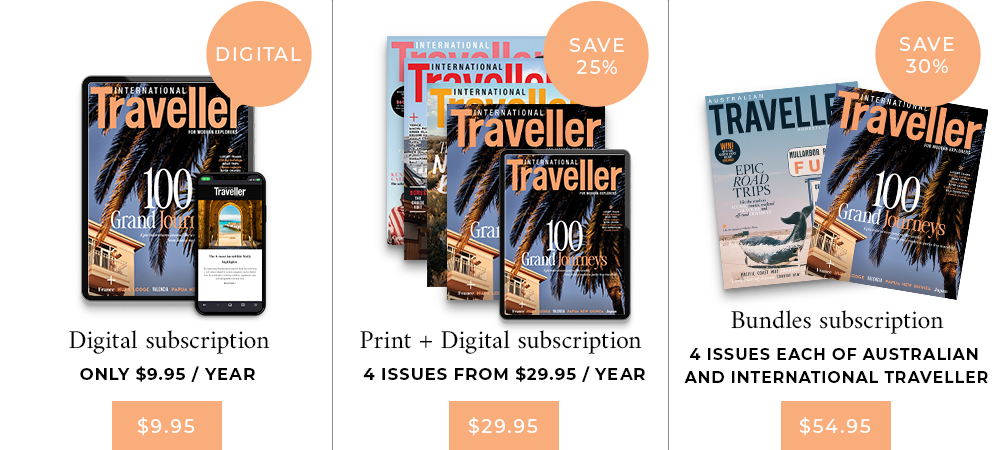

Reasons to see Mongolia now before it changes forever

A herd of horses roam freely across the Mongolia's wide open spaces (photo: Billy Bolton).

A swathe of ferocious deserts and epic mountains sandwiched between China and Russia, Mongolia is one of the world’s last true wildernesses.

But with a new airport due to open, now could be your last chance to see it before it changes forever.

As we sit outside our ger (yurt) staring across the blankness of the Gobi Desert, it could be any time within the last 600 years. Puje is grinding up leathery mutton from her own herd into a fine powder to season the potato stew she’ll serve tonight, while her red-cheeked children tumble over each other in the dust, taking it in turns to play the country’s combative forefather Chinggis Khan (Genghis to you and me).

Suddenly 50 horses flow over one of the flying-saucer-shaped hills. Three men direct them with guttural cries and flicks of slender switches towards a makeshift pen. Their homemade lassoes and long coats with golden sashes are everything I’d imagined from this ancient culture of herders. The fact they are straddling motorcycles rather than stallions is more of a shock.

The Ulaanbaatar drain

The Land of the Blue Sky is in a state of flux. While many continue to herd like their forefathers, changing climate and the loss of state-funded animal feed after the collapse of the Soviet Union have forced more than 600,000 nomads (around 20 per cent of the population) to flock to the country’s largest city, Ulaanbaatar. Today, its dilapidated Soviet skyscrapers are surrounded by mushroom rings made up of thousands of gers, mostly without electricity or running water.

Mongolians have no word for community and newcomers adapt to urban life painfully. Children used to running barefoot on the rippling steppe play in the husks of burnt-out cars, while their parents struggle with the concept of money. They’re used to roaming self-sufficiently through a world without fences, but here they have to pay for their tiny patch of land and buy food.

Despite the changes, Mongolia, one of the most sparsely populated countries on Earth, should still be at the top of any adventurer’s bucket list. Within a few hours of leaving the city in the back of a beaten-up army truck, the smooth grey ribbon of road is replaced by bone-shaking dirt tracks. By the following day, these have disappeared entirely.

Ger-fect… Sleeping in a herder’s circular home, the ger (yurt), is a must when travelling across Mongolia (photo: Billy Bolton).

Over the next two weeks our driver, Nima, navigates the vast Gobi region by mysterious signs invisible to Western eyes. Born a herder, his connection with the landscape makes us realise just how out of touch with nature we’ve become, seeing the world through our screens like Plato’s prisoners watching shadows of reality on a cave wall.

He’s as skilled at sniffing the air for an approaching dust storm as he is spotting a well from several miles away. With deft swivels of the steering wheel he reveals mountainous chasms filled with rivers of ice and ferocious smudges of desert, as vacant as the sky above except for a few Bactrian camels with empty humps flopping to the side.

The welcoming nomads

Nomads are generally delighted to welcome strangers in exchange for good company and a few useful gifts such as soap. Their generosity and trust are humbling, and in a country where the mercury regularly swings from -40 to 40 degrees, it can mean the difference between life and death. Inside, their circular homes are as well organised as ships and built around black-sooted stoves.

A latticework of light wood tied together with horse hair ropes supports the felt exterior, low wooden boxes covered in vivid fabrics serve as beds, while a dresser, often painted bright orange with delicate depictions of clouds, holds their winter clothing. Everything is crafted by hand and expected to last – a far cry from the consumerist clutter that flows steadily from my house to the nearest landfill site, often after no more than a few uses.

After a sweltering day spent exploring the startling moonscape of the Flaming Cliffs, the weirdly eroded chasm where American explorer Roy Chapman Andrews found a clutch of dinosaur eggs in the 1920s, we pull up outside a ger in the Ömnögovi Province. A flock of cashmere goats, knee-high and with hoofs barely bigger than 50 cent coins, press their faces against the tent as if they’re listening.

A strain of music escapes from the crack around the door before fading like smoke into the starlit stillness: ‘After man make everything, everything he can, you know that man makes money to buy from other man. This is a man’s world…’

Inside, three generations of a family and several neighbours have gathered around a television set. They’re howling with laughter as a Mongolian singer, skin smeared with black face paint, impersonates James Brown performing his 1966 hit It’s a Man’s Man’s Man’s World.

Mongolia’s culture of herders is purely ancient, right down to the homemade lassoes (photo: Billy Bolton).

They press steaming bowels of tsutai tsai (tea stewed with milk from their own mares) into our hands before settling us on stools to watch the program. It’s a surreal moment that gives a glimpse of what a westernised future in Mongolia might look like.

The behemoth dunes of Gurvansaikhan

A few days later, in the Gurvansaikhan National Park, Nima leads us on camel back to the base of the Khongoryn Els. Perhaps it’s no coincidence after days of eating rice and mare’s milk that every image these behemoth dunes bring to mind is food related. They’re as smooth as mountains of soft brown sugar, stand in peaks like freshly whipped egg whites and ripple like the icing on an enormous Christmas cake.

After an hour’s exhausting scramble to the top, I’m almost moved to tears by the view (although admittedly this could also be related to the fact that I am seriously dehydrated). It’s sunset and herds of horses and camels meander across the verdant plains which stretch as far as the eye can see. The only sign of humanity is a collection of three gers on the horizon. It’s like I’m looking at the world at the dawn of time, fresh, pure and full of promise.

With adventure travel becoming ever more popular, Mongolia’s tourism industry is gathering steam. International hotel chain Shangri-La became the most luxurious option in the country when it opened in 2015 and although there is essentially no high-end accommodation outside Ulaanbaatar, the Mongolian has have announced plans for several new hotels.

An enormous airport due to open next year will make it more accessible than ever before, but an influx of tourists is likely to have a significant impact on traditional culture. It seems that now is the time to experience Mongolia – before it changes forever.

Details: see Mongolia

Getting there: Fly to Mongolia from Australia via Beijing with Qantas and Mongolian Airlines, or via Hong Kong with Cathay Pacific and Mongolian Airlines. The Trans-Siberian Railway also links Ulaanbaatar with Moscow and Beijing.

Staying there: If luxury is a priority in Ulaanbaatar, stay at the Shangri-La. For a good value boutique alternative, try Urgoo.

Playing there: Most people set up tours when they are on the ground rather than pre-booking them, as they tend to be far cheaper. Hotels and hostels are good places to enquire at, even if you aren’t staying there. If you want to pre-book, try Sunpath Mongolia’s Golden Gobi tour.

LEAVE YOUR COMMENT