Dive into the coastal cities of Southeast Asia onboard Norwegian Jewel

Southeast Asia is dotted with coastal cities that burst with vibrant cultures, foods, traditions and rituals. A cruise through the region is guaranteed to reframe your sense of perspective.

From my balcony onboard the Norwegian Jewel, I watch as the ship hews a path through the South China Sea, leaving the mountainous archipelago of the Philippines behind us. I’m mesmerised – by the waves that fold in on themselves endlessly. By the gentle heave of the ship as it rides the ocean’s eternal pulse.

And by the unfathomable depths beneath us, so vast that it weaves my mind in mariner’s knots to merely imagine it. Earlier, I’d snorkelled in the impossibly turquoise waters off Palawan. Schools of tiny fish flitted past my goggles, an iridescent microcosm of the world hidden beneath the water’s skin.

Looking out at the boundless vista, I picture the centuries of seafarers who came before me, marvelling at the limitless planes of water as I do now, soaking in the sublime as they shrank before the immensity of the ocean. There’s a reason the oceans are known as The Free Seas – and it’s tied to the very waters Norwegian Jewel is traversing in this moment.

Bed down at the balcony stateroom onboard Norwegian Jewel.

In the Age of Discovery, Portugal claimed a monopoly over the trade routes to the Spice Islands of Southeast Asia. The seas, they argued, could be asserted as their territory, just like the land. But Dutch theologian Hugo Grotius disagreed. “The sea is so limitless,” he wrote in his 1609 treatise, “it cannot become a possession of anyone”.

This document, entitled Mare Liberum (The Free Seas) would become a foundational principle of international law. I’m certainly no expert on maritime legal philosophy. But as I sit on the ship, margarita in hand, feeling the warm sea breeze whip my hair around my face, I understand what Grotius was getting at. How could the seas be anything but free?

The ship traces the Philippine archipelago of Palawan. (Image: Eibne Saliba)

Norwegian Jewel returns to Asia

I’m onboard Norwegian Jewel amid Norwegian Cruise Line’s return to Asia after a three-year hiatus from the continent. I’m on a journey to visit some of Southeast Asia’s off-the-beaten-path ports and in doing so, hoping to unravel more about my own Peranakan heritage.

Peranakans are the descendants of the first waves of South Chinese settlers who migrated across maritime Southeast Asia, namely to Malaysia and Singapore, where they carried their rich culture and traditions. Although half of my family hails from this part of the world, the cruise marks my first time travelling in the region since I was a teenager.

The Norwegian Jewel is once more offering sailings in Asia.

Meeting tribes in Malaysia

In Kota Kinabalu, the heat engulfs me like a python wrapping itself around prey. When I disembark the ship, a beautiful woman wearing a traditional Bornean dress and flowers in her hair places a beaded necklace over my head. “Welcome to Sabah,” she says, smiling.

Sabah is a state on the Malaysian side of Borneo, home to 33 Indigenous groups that speak over 50 dialects. The descendants of five major tribes built traditional longhouses at Mari Mari Cultural Village, as a way to showcase the Indigenous way of life to visitors. It’s here that I learn more about the origins of the beautiful necklace gifted to me.

Beading is a traditional craft of the Rungus tribe in Borneo. (Image: Elizabeth Whitehead)

Our Mari Mari guide, Steph, explains, “Each tribe practices different crafts that are unique to them. For the Rungus tribe [one of the biggest in Sabah], that includes blacksmithing, making honey and beading”. Steph gestures to a woman adorned in intricate beadwork, vibrant sashes of colour crisscrossing on her chest. “The beads tell a story,” Steph says. And as I look closer, the motif of a human figure embedded in the woman’s jewellery comes into focus. Lizards and flowers are other common symbols, I learn, and the designs are passed down over generations.

The Dusun tribe make rice wine by hand. (Image: Elizabeth Whitehead)

Everything at Mari Mari has a fascinating story behind it, like the bamboo and rattan longhouses of the Rungus tribe that grow with their inhabitants (when the family expands, the house is simply extended with another room added on to the end). Clothing is intricately crafted by the ferocious (ex) head-hunter Murut tribe, the material painstakingly processed from the bark of trees native to the region. I watch as a man sits stoically, scraping wood to make barkcloth.

Mari Mari Cultural Village showcases the crafts and lifestyles of five different Indigenous tribes.

He’s wearing a necklace made from animal bones and a marvellous headdress of pheasant feathers that adds at least another foot to his stature. Sweet rice wine is handmade by the Dusun tribe, and I sample some from bamboo stems that serve as perfect shot glasses.

All around us, the jungle is a shade of green so deep and rich that it feels as if I’m looking at everything through an empty wine bottle. The plants are bigger in scale; Jurassic-like and alienesque. Plump raindrops begin to fall, hitting outstretched leaves with a satisfying splat – it’s our signal to find shelter before the afternoon downpour.

Stalls overflow with colourful fish. (Image: Elizabeth Whitehead)

Meandering through Kota Kinabalu markets

Later, our tour group travels from the jungle to the sea to peruse Kota Kinabalu’s night markets. Stalls overflow with vegetables and colourful fish, still slick and glossy from the ocean. Vendors preside over steaming vats of umami-rich laksa, and the air is thick with the acrid smoke of meat skewers cooking on the barbecue.

Laksa is a typical Malaysian dish.

The smells, sights and sensations remind me of the food I ate when visiting family in Malaysia; fresh seafood and plates of deep-fried crab; pandan leaves heavy with coconut-infused nasi lemak; coolers full of refreshing iced Milo (a distinctly Malaysian take on the classic drink I firmly believe needs to be adopted into Aussie cafes). It’s an olfactory journey back in time.

Fresh seafood at Kota Kina.

Sea days reign supreme

I’m surprised to find that some of my favourite days on the cruise are the ones spent entirely at sea. I retreat to the thermal spa located at the ship’s forward and spend hours soaking in the hot tub, surveying the sea through the spa’s floor-to-ceiling windows. I simply appreciate the liminality of it all, the feeling of in-betweenness in space and in time.

The open ocean is the only expanse of Earth I can think of that has remained unchanged over centuries, let alone millennia. Out here, one can just as easily imagine life through the eyes of a marauding pirate or an intrepid explorer in the Age of Navigation. I watch as we carve our way through the water – the sea’s sole witness, save for a lone seabird that travels alongside us for a while, drawing circles in the sky.

A taste of rural life in Vietnam

We’re driving through the rural streets radiating from Nha Trang in Vietnam when our guide, Liem, abruptly stops the bus. He’s spotted a herd of water buffalo grazing in a rice paddy by the road. “It’s your lucky day,” Liem grins, ushering us onto the roadside. “Watch this,” he says, cupping his hands over his mouth before letting out a protracted, ear-splitting yowl akin to the caterwaul of an angry cat. A few startled buffalo look up in confusion.

Liem bellows once more, even louder this time, and the buffalo take off, stampeding across the rice paddy and running towards the mountains in the distance. Baby buffalo splash their hooves in the mud as they scamper behind their mothers. A few perturbed egrets follow suit, evacuating the rice paddy and vanishing to white dots in the cloudless sky. There’s a second of silence before our group bursts into laughter. “They look aggressive,” Liem says of the buffalo, the distant thud of their hooves still audible, “but they are actually very charming animals”.

Liem is perhaps one of the most jovial people I have ever met. Born and raised in Nha Trang, Liem is leading a shore excursion to showcase a slice of rural life in the region. “The most important thing is that you are happy,” he philosophises as we drive through sprawling rice paddies on the way to Linh Quang Pagoda, a place of Zen Buddhist worship.

Fishing boats bob in the harbour of Nha Trang.

Blue Chinese dragons perch atop the pagoda’s sloped roof, and a small gecko sunbakes on the step like the mortal counterpart to the mighty reptilians. Bonsai trees and bougainvillea dot the garden, and a large statue of Guanyin, the Chinese goddess of compassion, looms over the graveyard.

“Once a year, villagers come here to sweep the graves of their family and honour their ancestors,” explains Liem. It’s a festival tradition I remember from childhood, when my family and I would burn golden joss paper, or ‘spirit money’, to send to our ancestors in the realm of the dead.

Inside the pagoda, the musky smell of incense fills the room. Offerings of water, biscuits and fruit are laid out before golden statues of the Buddha. A female monk with kind eyes greets us, and gifts each one of our party an offering from the table. She gently clasps the hand of Sharon, a passenger on the excursion, and confides something to Liem in Vietnamese.

“She tells me she is so happy you are all here,” Liem translates, “it’s very rare that she sees foreigners here.” The monk smiles at us, before leaving to pray. We stay a while, listening to the rhythmic murmur of her chanting overlaid by the resounding hum of the singing bowl she strikes intermittently. A sense of serenity remains with me long after I leave the pagoda, just like the smell of incense that lingers on my clothes.

A monk lights incense before praying at Linh Quang Pagoda in Vietnam. (Image: Elizabeth Whitehead)

Ancestral ties in Singapore

Singapore marks the terminus of our cruise. Here, I divert my attention from the meridians of the ocean to the meridians of my body at a Traditional Chinese Medicine clinic. Having grown up around family who practice qi gong and keep a medicine cabinet well-stocked with herbal remedies, I’ve been curious to experience an Eastern approach to wellness while I’m here.

On account of my tendency to slouch and the consequent tightness in my shoulders, the doctor has prescribed me a full-body tui na massage with lavender essential oil, where a practitioner pinches, kneads and presses my acupressure points to stimulate the flow of qi (life force) through my body.

It’s followed up with a round of acupuncture in my upper back. I grit my teeth as the doctor pushes hair-thin needles through my skin, but the feeling is unexpectedly euphoric – like a warm river coursing through my shoulders. When I leave, I’m standing straighter than I have in years.

Singapore’s Chinatown is festooned with colourful lanterns.

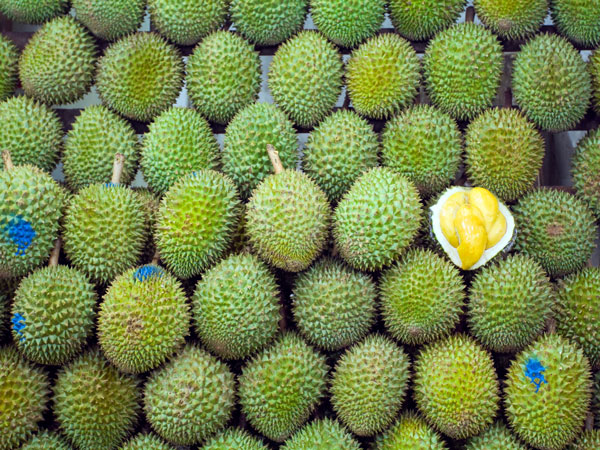

The rest of the day is spent mulling around the streets of Chinatown, which are festooned with red lanterns and vibrant shops chock-full of curious items. I set about acquiring keepsakes; brass baoding balls that I rotate in my hands when I’m stressed; an embellished hairstick to pin my hair out of my face; and enough herbal ointments, oils and balms to last a lifetime of ailments. But the greatest treasures I find are at a fruit stall, where I gorge on ripe mangosteens and plump segments of custard-like durian fruit, plucked from a 100-year-old tree.

Singaporean Durian is characterised by its strong smell and taste.

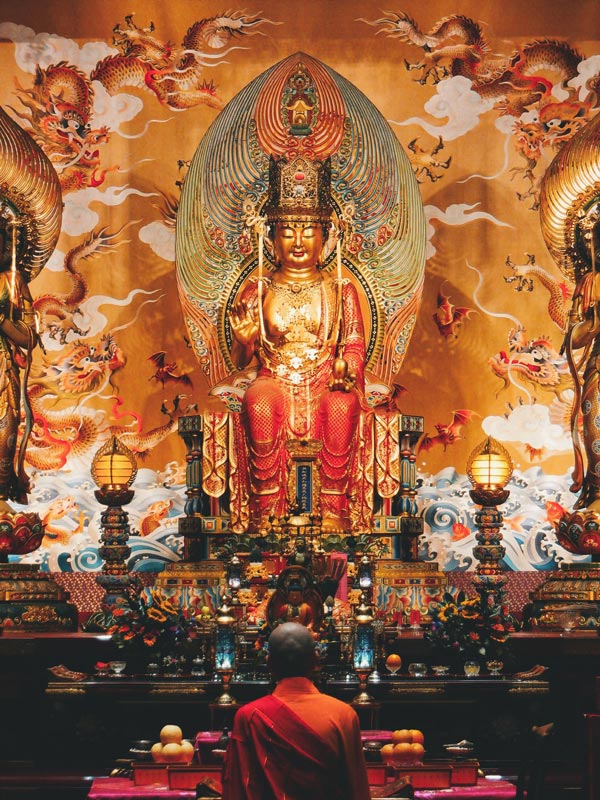

With my sweet tooth sated, I visit the Buddha Tooth Relic Temple in the heart of Chinatown, stepping into a yawning chamber of red and gold. Thousands of repeating Buddha statues adorn the walls. I feel as if I’m being watched over – literally. I learn that these are depictions of the cosmic Amitābha Buddha, the Buddha of the Pure Land and the guardian of my Chinese zodiac.

The golden interior of The Buddha Tooth Relic Temple in Singapore. (Image: Carson Arias)

It’s a synchronicity that compels me to purchase a tray of flowers and a lamp to leave as an offering. The woman selling the flowers hands me a pen, and instructs me to write my family name. “That way, the offering will be for your ancestors, too”.

I do, and place the tray at the shrine, contributing one more light to the dozens compounding the warm, honeyed glow of the temple. Taking a cue from the other devotees placing down offerings, I kneel to say a short prayer for my ancestors. I’ve never known much about who they are. But after the last week of travelling, I feel connected to them nonetheless.

The Buddha Tooth Relic Temple in Singapore is a hub for devotees of Chinese Buddhism. (Image: Lily Banse)

A traveller’s checklist

Norwegian Cruise Line offers a variety of cruises in Asia. Sail on Norwegian Spirit, hopping between the white-sand beaches of the Philippines, ancient temples of Vietnam and the delicious foodie markets of Malaysia. You’ll spend 14 days onboard, jumping off at numerous ports to explore the wonders of Asia, departing from Taipei, Taiwan in December 2024.

The turquoise waters of Boracay in the Philippines. (Image: Laimonas Keseriauski)

Step aboard Norwegian Sky and the only thing you’ll have to worry about is snagging a lounger a toe’s-dip away from the pool. When you can pull yourself away from the ship’s incredible facilities, jump off at a variety of international ports for Malay cuisine, Islamic art and Buddhist culture. Departing from Singapore in February 2025.

LEAVE YOUR COMMENT