Life on the Mekong: Finding connection on a cruise from Cambodia to Vietnam

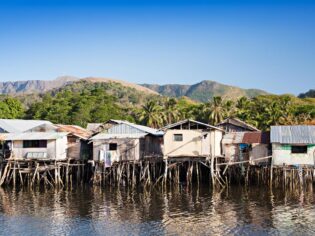

Stilt houses on the Mekong. (Image: Getty/Saiko3p)

The richness of a river cruise along the Mekong is found in the genuine cultural connection it fosters, from Cambodia to Vietnam.

The sun is still low in the sky, but already the humidity is making my skin glisten. Locals will tell you there are only two temperatures here, and they’ll say it with a pitying giggle: hot and bloody hot.

Stilt houses cling to the banks. The occupants have taken to their sampans (flat-bottomed wooden boats), beginning their chores before the heat forces them back inside. Already, a nón lá (conical hat) is essential.

This is the Mekong Delta, and we’ve just crossed from the peaceful, almost empty river of Cambodia into a hotbed of life in Vietnam overnight. Not without some drama, too: the sudden increase of larger boats guarding the border crossing made it feel something like a game of bumper cars.

Stilt houses on the Mekong. (Image: Getty/Saiko3p)

I’ve already been to the dining room of AmaDara – AmaWaterways’ river cruise ship taking guests from Siem Reap in Cambodia all the way down the Mekong River to Ho Chi Minh in Vietnam – for breakfast and am now sitting on the private deck of my spacious room with a tea.

The AmaDara on the Mekong. (Image: Kassia Byrnes)

I’m embracing the Vietnamese tea ceremony way of making my morning brew a mindful moment, as we’d been taught by the ship’s local wellness director, just the night before.

Onboard the luxury cruise. (Image: Kassia Byrnes)

I can’t get over how quickly the scenery has changed. Just days ago on a shore excursion, I was being welcomed into the shade under 79-year-old Hon’s typically stilted house in the small Cambodian village of Angkor Ban.

We’d already been invited to walk through the open-plan house above us. Several generations of family pictures proudly displayed on the wall above the bed. Kitchen packed to the rafters with silver pots and pans. All the hallmarks of most houses around the world, really.

Except, perhaps, for the bamboo floors with just enough of a gap between the slats to allow a breeze through on this 35-degree day.

Then we went back under the house – the main place Cambodian families spend their time at home during the day – to sit on a wooden bench. I was fanning myself with the $1 fabric fan I had picked up previously at a rest stop out of desperation to beat the heavy heat.

Inside Hon’s home. (Image: Kassia Byrnes)

Hon’s neighbour, 64-year-old Ry, wandered up to us to see what the gathering of visitors was all about. Our Cambodian tour guide, Tek, struck up conversation with her, translating to the rest of us that he had cheekily asked who she fancied in our group.

Given the group’s average age was probably about 50, it was a surprise when she pointed directly to me, 30-odd years her junior, before speaking in Cambodian to Tek.

“She’s the tallest woman in the village,” he translated for me, “and she loves that you’re even taller.”

Taller I am, by at least a foot. A fact that becomes evident when I stand up for a classic back-to-back measurement. But she’s not wrong, she is by far the tallest local woman I have seen anywhere in Cambodia. And we tall women love to unite.

After chatting to the group at large for a little longer, she scuttled off, leaving me to damn myself for not getting a photo with my tall sister-from-another-mister. But shortly she returned with a camera phone of her own, pulling me in for a selfie. I obliged, before taking my own.

Then, she told our guide to share that she felt I was “perfect”. I hugged her and returned the compliment – it’s something that I meant from the bottom of my heart.

Not only because she looked cool as a cucumber while I was red-faced and ever-sweaty. But because in a country where only five per cent of the population are currently privileged enough to have made it over 60 years of age, due to the devastation of an entire generation by the Khmer Rouge, it’s truly an honour to meet her and Hon.

Just remembering this interaction is enough to give me goosebumps. It’s one of those sweet, fun travel connections that remind us we’re all the same, at heart.

Meeting Ry in Angkor Ban. (Image: Kassia Byrnes)

Ry was obviously my favourite person in Cambodia. Still, it’s a difficult feat considering the number of incredible people I met. The carefully curated shore excursions, and even free time, went beyond tokenism and fostered very real connections and mutual cultural exchanges that touched me in a way I simply wasn’t prepared for.

Many of them touch on the effects of the Khmer Rouge, the radical communist movement that was responsible for the genocide of nearly a quarter of Cambodians in the 1970s, still keenly felt half a century later.

From the giant African rats of APOPO who help detect buried landmines (a life-saving endeavour given the visitor centre manager, Sambat, tells us there’s still an average of one death per week and that Cambodia has the highest amputee population per capita, with half of those affected being children) and the trainers who love them.

Giant African rats of APOPO help detect active landmines. (Image: Kassia Byrnes)

To the acrobats of Phare, The Cambodian Circus who graduated from Phare Ponleu Selpak’s vocational training centre; an association started by nine survivors of the Khmer Rouge who saw a need to teach new skills to the poor and socially deprived young people of their city.

A young Buddhist watches on quietly. (Image: Kassia Byrnes)

To another of our Cambodian tour guides, Ray, who was incredibly proud of the dramatic carvings and intricate buildings of Angkor’s temples but remained nervous about being honest with his political opinions in public. But who freely shared the frustration of younger Cambodians when our group returned to the bus.

Novice monks at Phnom Pros Monastery. (Image: Kassia Byrnes)

To the young schoolchildren of Oknhatey village, who raced behind my ambling ox cart ride that returned me to the ship, just for the thrill of it. Asking me any and all questions they’d learned in English.

To the young monks-in-training banging a drum out the front of Phnom Pros monastery – a beautiful building that was turned into yet another prison by the Khmer Rouge, the closest killing field in the valley below, and reclaimed once the war ended.

A young monk in training beating a drum at Phnom Pros. (Image: Kassia Byrnes)

To the graduated monks blessing our group during a moving ceremony of water and flowers in the shadow of a giant Buddha statue and intricate decorations inside Vipassana Dhurak Buddhist Centre.

To the principal of Chong Koh Oknhatey Primary School, Nov Sem, who received no funding or payment to restart the school in 1980 after the war had forced it to close. But did it anyway, to great success.

The principal of Chong Koh Oknhatey Primary School, Nov Sem. (Image: Kassia Byrnes)

To Bou Meng and Chum Mey, two of only seven known prisoners to survive the torture and murder of at least 122,739 people at S-21 in Phnom Penh. Today, they sell their memoirs to travellers visiting the eerie grounds of this tragic place.

Sharing how they utilised their artistic and sewing machine repair skills, respectively, to make themselves indispensable to the Khmer Rouge. Other visiting Cambodians showed them an obvious reverence and respect that went beyond a typical respect of elders.

It’s these connections, and many more, that made Cambodia for me. Ray summed it up perfectly when he told us on a solemn walk through the most infamous Phnom Penh killing fields that, “Cambodian people will never forget those two years, three months and 18 days. We lost so much. But we still forgive.”

He explained Cambodians managed to come out the other side still finding it within themselves to champion the four main Buddhist principles that the majority of the country follows: kindness, compassion, sympathy and community. And it’s abundantly clear. All this before we even crossed the border into Vietnam.

River scenes in Cái Bè. (Image: Kassia Byrnes)

Over the next few days before we reach Ho Chi Minh City and part ways, we will see beautiful traditional dance performances onboard, watch silk weavers making their intricate fabrics, wave to captains transporting their crops in over-laden boats, help candy-makers cook rice paper in Cái Bè and beg a ride on the back of a rickshaw.

In another small village, the farming island of Tân Châu, we will be invited into another home by an elderly couple. We’ll walk through, comparing the differences and similarities to what we saw in Angkor Ban, while their young granddaughters practise TikTok dances in the yard outside. They’ll have quickly lost interest in the strangers talking to their grandfather.

The village of Angkor Ban. (Image: Kassia Byrnes)

Here, I will meet the elderly matriarch of the home when she shows us around her kitchen. With absolutely no English and no one to translate for us this time, she will still manage to clearly communicate, by pointing and finger-waggling, that she is not a fan of my nose ring.

The matriarch of the Vietnamese family. (Image: Kassia Byrnes)

Not quite the same sentiment as Ry had shared, but one that sounded exactly like my own grandma. You see? We’re all the same at heart.

And her home in Tân Châu. (Image: Kassia Byrnes)

A traveller’s checklist

Getting there

Singapore Airlines, Vietnam Airlines, Malaysia Airlines, Qantas and more fly from Australia to Siem Reap with a stopover in Ho Chi Minh. Or fly direct to Phnom Penh and catch a six- to seven-hour bus.

Playing there

AmaWaterways’ Riches of the Mekong seven-night cruise runs January-April and August-December in 2025, with options to extend your tour before or after the cruise in Siem Reap and Ho Chi Minh City. From $3465 per person, including all onboard meals and all touring. Gratuities not included.

Most staterooms on AmaDara feature balconies. (Image: Kassia Byrnes)

LEAVE YOUR COMMENT