How NOT to treat animals on a luxury safari

The landscape of Samburu National Reserve in Kenya holds a dramatic beauty.

On a luxury Kenya safari in Samburu National Reserve, observing the relationship between man and beast leaves us wondering, just who are the bigger animals? Writes Dilvin Yasa.

Standing atop the Jeep in a safari-style jacket and white surgical mask, a man is lobbing apples at the head of a lion sleeping outstretched underneath the shade of a tree. Thud, it sounds as one hits the lion’s jaw. Thud, sounds another as it makes contact with the lion’s forehead.

“Sir, would you please sit down and stop throwing apples at the lions,” his guide hisses from the front seat, no doubt amazed he’s ever had to utter those words at anyone, but surgical mask man is also perplexed; after all, he didn’t pay his money to come on safari to photograph a sleeping lion, he spits. “I want to get a photo of it awake.”

In a deafening silence only occasionally broken with birdsong and hyena cackle – and, oh yes, the thuds – the rest of us expect to be viewing a (much-deserved) mauling any moment now, yet remarkably the lion doesn’t seem all that bothered, only sleepily raising his head momentarily before dropping it again.

The guide, however, has had enough. He takes the apples out of the man’s hands and as he begins to pull away, we hear the man cry, “There should be some sort of guarantee about animal behaviour on these things.”

When, bewildered, I look at my own guide, James, he simply shrugs and starts the ignition. “That’s nothing,” he smiles wryly. “Last week I had a French woman in the back who kept pointing out the baboons and laughing, ‘look James, there’s your relatives’.” We drive away in silence.

My trip to Samburu National Reserve, a handsome parkland located some 350 kilometres north of Nairobi, where the foothills of snow-capped Mount Kenya mesh with the northern desert has, up until this point, been the dream I’d always hoped it would be.

Checking into the elegant Elephant Bedroom Camp, located on the banks of the muddy Ewaso Nyiro River, I was overjoyed to discover that camping means a luxury tent with its own plunge pool, hot running water and four-course meals under a canopy of stars. A 6am wake-up call for a sunrise safari? Not so bad when coffee and biscuits are delivered to your door and over your waiter’s shoulder you can see herds of elephants and monkeys milling around.

Together, James and I have covered serious ground since I arrived two days ago, heading out on twice-daily, three-hour safaris at both sunrise and sunset (the animals all fall asleep under the hot midday sun, as do I). And although we have made our way through the stunning inclines of acacia trees teeming with curious giraffes ducking their heads into our Jeep for a closer look, or playful prides of lions wrestling with their cubs (the only animal that charges us is an overly aggressive cow, and that evening I eat my steak with much enjoyment), there is something unsettling that I can’t quite put my finger on.

Until I have what Oprah would call my ‘aha moment’ and I realise that, although I came to Kenya to watch wildlife, it’s often the behaviour of other humans (read: tourists) that gets my attention.

The humans I speak of, are plenty. Whenever we stop at a site to watch a herd of elephants play or to view some opportunistic hyenas pull apart the leftovers of a lion’s lunch (in this case, a very unfortunate zebra), a convoy of camper vans, Jeeps and SUVs – sometimes up to 10 in a row – hoon up to our spot, leaving us jostling for the best position to watch the animals.

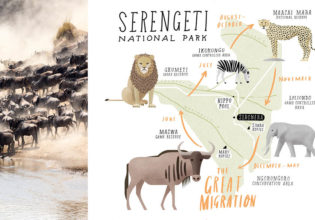

“Hey elephant! Over here mate!” “Oi baboon! Smile!” Papping the poor animal like it’s Kim Kardashian stumbling out of a bar, everyone begins shouting out (or throwing apples) to get its attention. It’s early May so it’s a quiet time to be on safari, but at the height of the Great Migration (from July onwards), it can be chaos.

“Sometimes you’ll find up to 100 vehicles circling a pride,” admits James who adds that he is torn between his love of promoting his homeland and wanting to protect his reserve – not only from the outsiders but even from those within his own village who can’t understand why they can’t bring in their own herds to feed on the reserve’s pastures. “But what can you do? That’s tourism for you.”

That’s not to say that increasing tourism is bad for Kenya – there have been plenty of positives since the country was put firmly on the map as a premier safari destination. Tourist numbers may be up, but happily, so too are the number of animals roaming the dramatic landscapes – a direct contrast to the rest of Africa where numbers of elephants and lions are decreasing at a rapid pace.

Today, Samburu is home to over 40 lions, the highest number in over a decade, and thanks to the work of foundations such as Save the Elephants, its elephant population, once in danger of extinction, is also growing steadily. I don’t mind admitting that I see so many herds during my visit that I eventually start thinking, ‘Yeah, yeah, another elephant’.

Increasing too are the number of luxury lodges that cater to those who prefer their safaris with a side of flash (achieved, it must be said, in the face of naysayers who insist Kenya is still sorely lacking in the kind of infrastructure needed to cater for a growing tourism market). I find the service at Elephant Bedroom Camp (and, later in my trip, at Maasai Mara’s Tipilikwani) to be exceptional, with wi-fi, gregarious staff and guards with sniper-like abilities to sniff out your torchlight at 1000 paces, since they are required to walk you to and from your tent to the dining quarters once the sun sets (many of those aforementioned creatures occasionally like to check in on how you’re going with those biscuits).

So far, so good, but now that the Kenyan authorities have cornered the luxury safari market and dramatically increased wildlife figures, what to do about those humans?

It’s a question that’s on everyone’s minds, admits James, who adds that the rangers within the reserve are currently working on strategies on how to deal with one of the biggest environmental disasters now affecting the park – the careless disposal of rubbish, including white surgical masks. “We find they often get thrown from moving cars and, of course, the animals all like to pick them up so it’s becoming a very real danger.”

Add to that the legions of holidaymakers now requesting ‘guarantees’ of animal sightings (“We had one woman demand her money back because she didn’t see a cheetah, which are the most difficult of the animals to spot,” James says), and those who like to interact with the locals by way of hail of fruit, and there seems to be a long journey ahead.

“All we can do is continue to educate people as we go,” says James as we sit sipping tea, surrounded by monkeys eyeing my bread basket. “Education is everything and that’s as true here as it is anywhere else.”

Details: Samburu National Reserve luxury safari

Getting there: South African Airways offers direct flights to Johannesburg from Perth, with connecting flights to Nairobi (codeshares available from major Australian cities).

Playing there: Book your own Kenya trip with Swagman Tours.

Find out more: For more information on Kenya, visit Magical Kenya.

LEAVE YOUR COMMENT